Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: Depression and anxiety are common among patients having total hip arthroplasty (THA) and are linked to worse postoperative results. Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic with antidepressant effects and has gained popularity as a perioperative treatment for mental conditions like major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

Objective: To evaluate whether intraoperative ketamine administration improves short-term postoperative mental health outcomes in THA patients with preexisting MDD and/or GAD.

Methodology: A retrospective cohort analysis was conducted utilizing TriNetX’s Global Collaborative Network, with 152 healthcare institutions analyzed. We included adult patients (≥18 years) receiving THA with diagnoses of generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, or depressive episode. Two cohorts were formed using 1:1 propensity score matching to compare age, gender, and other characteristics. The cohorts included patients who received intraoperative ketamine (n = 21,394) as well as those who did not. Depressive and anxiety episodes, as well as psychiatric drug use, were monitored and studied throughout a 90-day postoperative period.

Results: Compared to the controls, the ketamine group had a significantly higher risk of depressive episodes (24.9% vs. 20.2%; risk ratio [RR] 1.24; odds ratio [OR] 1.31; hazard ratio [HR] 1.28; p<0.0001), anxiety disorders (22.7% vs. 17.6%; RR 1.29; OR 1.37; HR 1.34; p<0.0001), and psychiatric medication use (38.6% vs. 35.8%; RR 1.08; OR 1.13; HR 1.09; p<0.0001).

Conclusion: Our study showed that intraoperative ketamine was associated with a higher short-term risk and earlier onset of postoperative psychiatric symptoms in patients with a history of depression or anxiety undergoing THA. These findings challenge the previous literature on ketamine’s perioperative psychiatric benefits and highlight the need for further prospective studies.

Keywords

Depression, Anxiety, Ketamine, Psychiatry, Total hip arthroplasty.

Introduction

Depressive and anxiety problems are common in patients undergoing major orthopedic procedures like total hip arthroplasty (THA). Emerging data suggest that psychiatric comorbidities have a major impact on surgical outcomes. Specifically, prospective studies have demonstrated that individuals with preexisting anxiety or depression derive less postoperative improvement in pain and function and experience a higher incidence of adverse events following THA compared to those without such diagnoses.[1] A comprehensive systematic review of 30 studies further revealed that patients with depression undergoing total joint arthroplasty had increased rates of hospital readmission, discharge to non-home settings, persistent postoperative pain, revision surgery, and elevated healthcare costs.[2] These findings are echoed by additional investigations showing that preoperative depression correlates with longer hospital stays, higher risk of readmission, prosthetic joint infection, and the need for revision arthroplasty.[3] Collectively, this body of literature underscores the substantial impact of psychological health on perioperative and postoperative recovery in orthopedic populations.

Postoperative depression is associated with severe pain, cognitive dysfunction, prolonged hospitalization, and increased morbidity.[4] Patients with a prior history of depression or anxiety may be particularly susceptible to these complications, with evidence suggesting that preoperative psychiatric illness not only increases the risk of postoperative depressive episodes but may also exacerbate their intensity.[4]

Ketamine is a phencyclidine-derived drug initially used as an anesthetic in the 1960s. It has sparked interest because of its psychedelic properties. In addition to its dissociative anesthetic and analgesic characteristics, ketamine has shown fast and prolonged antidepressant action.[5] A pivotal clinical study published in 2000 reported that a single low-dose intravenous infusion of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) resulted in rapid-onset and durable antidepressant effects in patients with treatment-resistant depression.[5] Subsequent randomized controlled trials have replicated these findings, confirming ketamine’s reproducibility in alleviating depressive and anxiety symptoms.[6] Ketamine functions primarily as an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist. This blockade is believed to induce a glutamate surge, subsequently activating α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors, and initiating downstream signaling cascades involving mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which together promote synaptic plasticity and reverse stress-induced neural deficits.[7,8]

Given the established link between preoperative psychiatric illness and poor surgical outcomes, investigating ketamine’s perioperative impact among THA patients with preexisting depression or anxiety may inform anesthetic strategies aimed at mitigating postoperative complications and enhancing recovery.[2]

Methodology

A retrospective cohort study utilizing data from TriNetX Global Collaborative Network, aggregated de-identified electronic health records of over 117 million patients from 152 healthcare organizations across the United States. The final matched population consisted of 42,788 patients, divided into two cohorts: 21,394 in the intraoperative ketamine cohort and 21,394 in the control cohort. The population that was studied was adults (≥18 years) who underwent primary THA between January 1, 2020, and January 1, 2025, using the current procedural terminology (CPT) code 27130. Patients who were eligible for surgery had a documented diagnosis of major depressive disorder (International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10: F33), depressive episode (F32), or generalized anxiety disorder (F41.1) during the previous year. Exposure was characterized as receiving intraoperative injectable ketamine administration, whereas the control group had no recorded ketamine exposure during hospitalization for THA.

Each cohort received 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching without replacement, along with a caliper width of 0.1 pooled standard deviations. Covariates included age, sex, baseline psychiatric diagnoses, and prevalent comorbidities, which resulted in balanced cohorts. Three outcomes were assessed over a 90-day postoperative period: (1) incidence of new or recurrent depressive episodes, (2) incidence of new or recurrent anxiety disorders, and (3) psychiatric medication use (SSRIs (ATC N06AB), bupropion (RXNORM: 42347), or antipsychotics (ATC N05A)).

Statistical studies used OR, RR, and HR with 95% confidence intervals. Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests were used to examine time-to-event outcomes. A p-value of <0.05 was judged statistically significant. All studies were carried out utilizing TriNetX’s built-in analytics tools, with data that was de-identified and health insurance portability and accountability act (HIPAA)/ general data protection regulation (GDPR) compatible.

Results

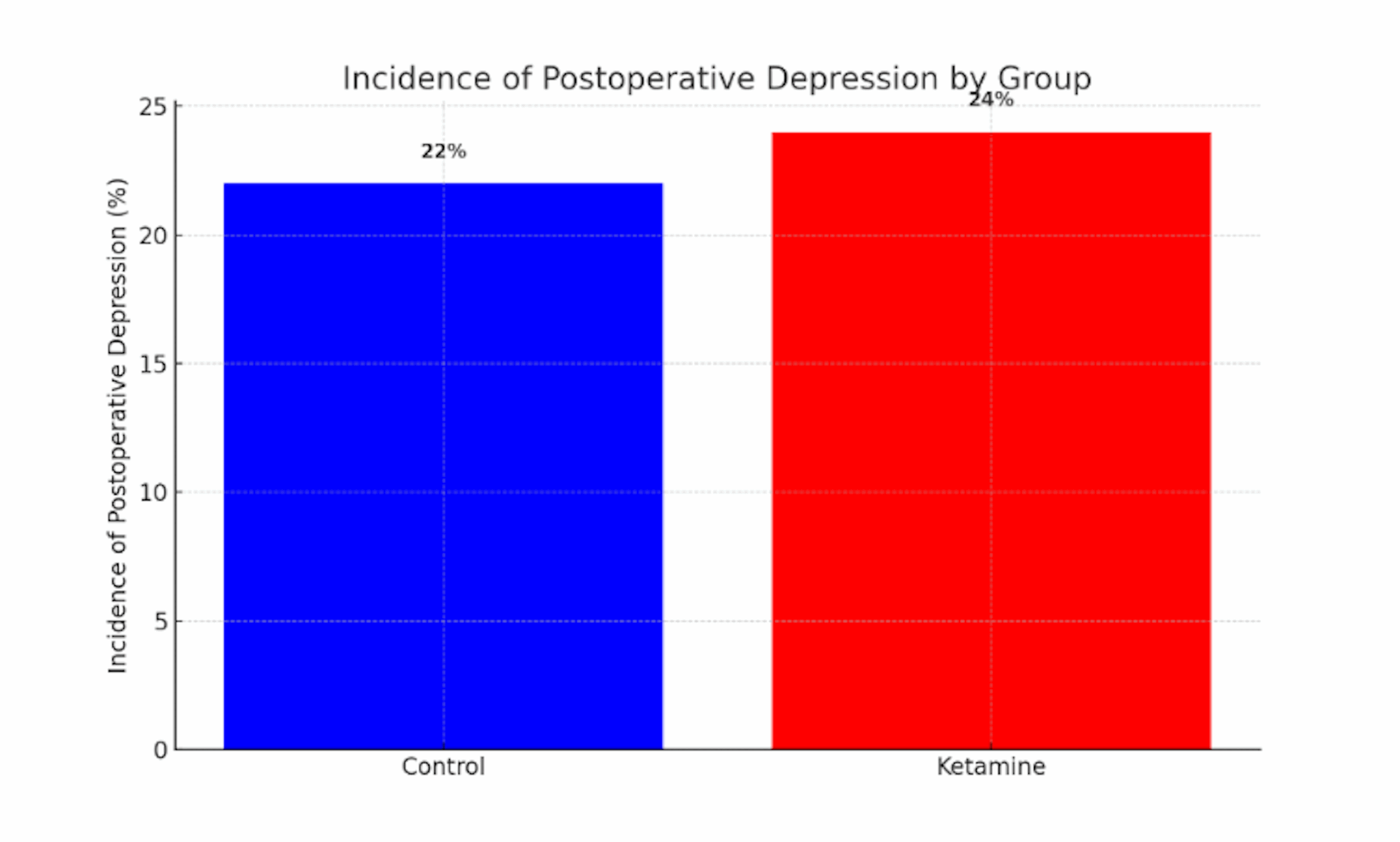

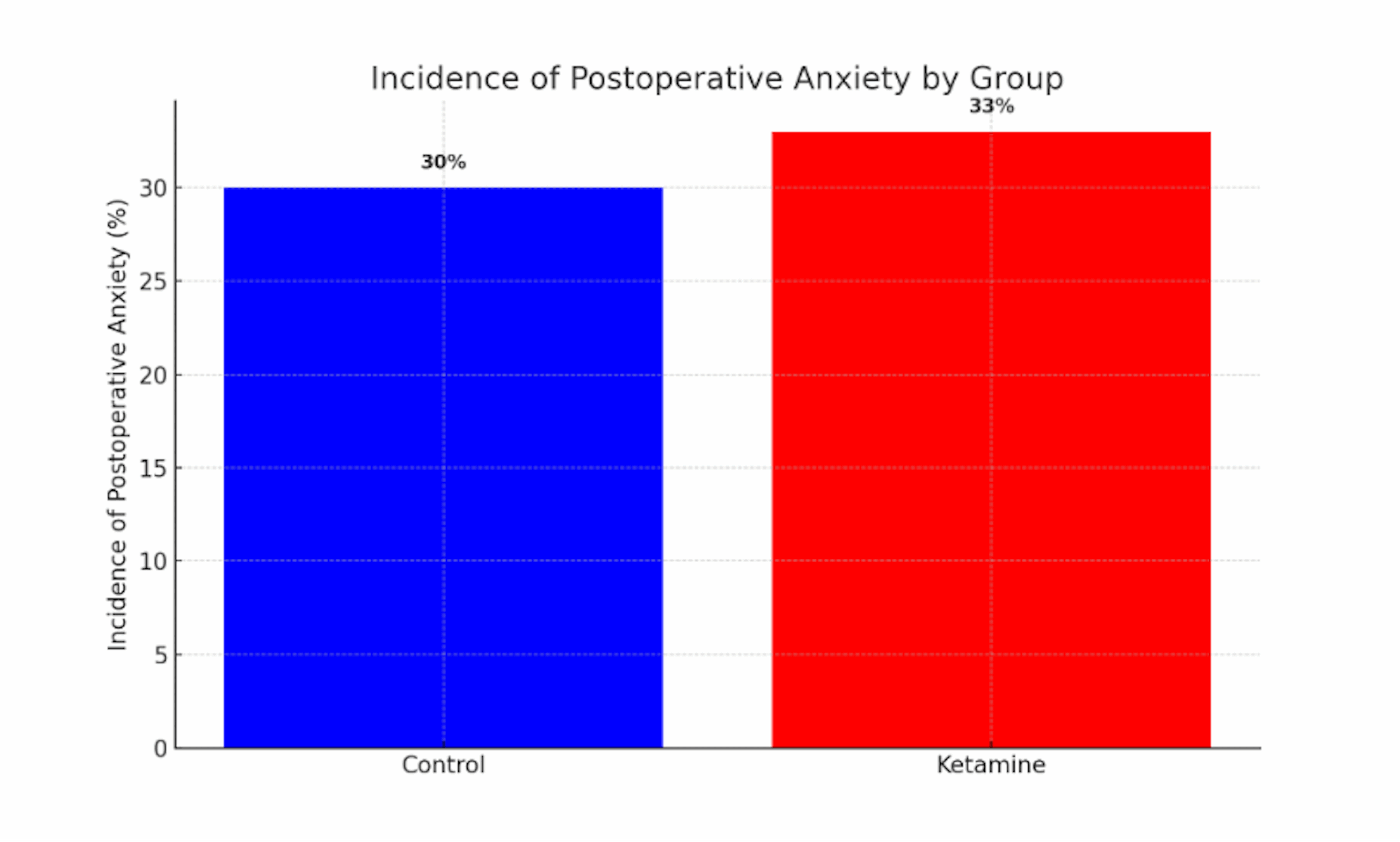

In this retrospective cohort of 42,788 patients with preexisting mood disorders undergoing THA, we observed no substantial overall reduction in postoperative psychiatric complications with intraoperative ketamine. The incidence of documented postoperative depression was similar between the ketamine group and controls (approximately 24% vs 22%, respectively), with the ketamine group even showing a slight numeric increase in depressive episodes (RR ~1.09, P> 0.05). Likewise, the incidence of postoperative anxiety symptoms did not significantly differ (around 33% vs 30% in ketamine vs control). Statistical comparisons yielded no clinically meaningful advantage of ketamine in preventing postoperative depression or anxiety in the general cohort. Although p-values for group differences in depression and anxiety incidence were below 0.05 (owing to the large sample size), the absolute risk differences were marginal (on the order of 2–3%), suggesting limited practical significance. In summary, intraoperative ketamine did not achieve the hypothesized reduction in postoperative depression and anxiety rates in this high-risk surgical population.

Subgroup analyses stratified by age, sex, and mental illness found no significant impact of modification, confirming the main findings. When stratified by age, patients under 65 and those 65 or older experienced comparable outcomes: ketamine’s impact on mood symptoms was minimal in both groups. There was a trend toward a slight reduction in depressive episodes among younger patients given ketamine (e.g., 18% vs 20% in controls under 65). Still, this trend did not reach significance after adjusting for covariates. Older adults (≥65) similarly showed no benefit from ketamine (with nearly identical depression incidence ~25% in both subgroups). No interaction was found between sex and treatment: male and female patients derived similarly negligible benefit from ketamine. The rate of postoperative depression in women was slightly higher overall than in men, but within each sex, ketamine had no appreciable effect on reducing that risk. Likewise, ketamine’s effect on anxiety did not differ between men and women. Notably, stratification by psychiatric diagnosis (major depressive disorder vs generalized anxiety disorder) suggested some nuanced patterns. Patients with primary MDD who received ketamine showed a minor, non-significant decrease in subsequent depressive symptom flares compared to depressed patients who did not receive ketamine (e.g., 26% vs 28%). In contrast, among patients with GAD, the ketamine group had a slightly higher incidence of postoperative anxiety episodes than controls (for example, 34% vs 30%). However, this difference was also not statistically significant. There was no evidence that ketamine prevented the onset of new mood episodes in patients who had only one of the diagnoses (i.e., no crossover preventive benefit: ketamine did not significantly reduce depressive episodes in those with anxiety disorder alone, nor anxiety flares in those with depression alone). These subgroup findings underscore that no demographic or diagnostic category showed a clear benefit from intraoperative ketamine in terms of postoperative mental health outcomes.

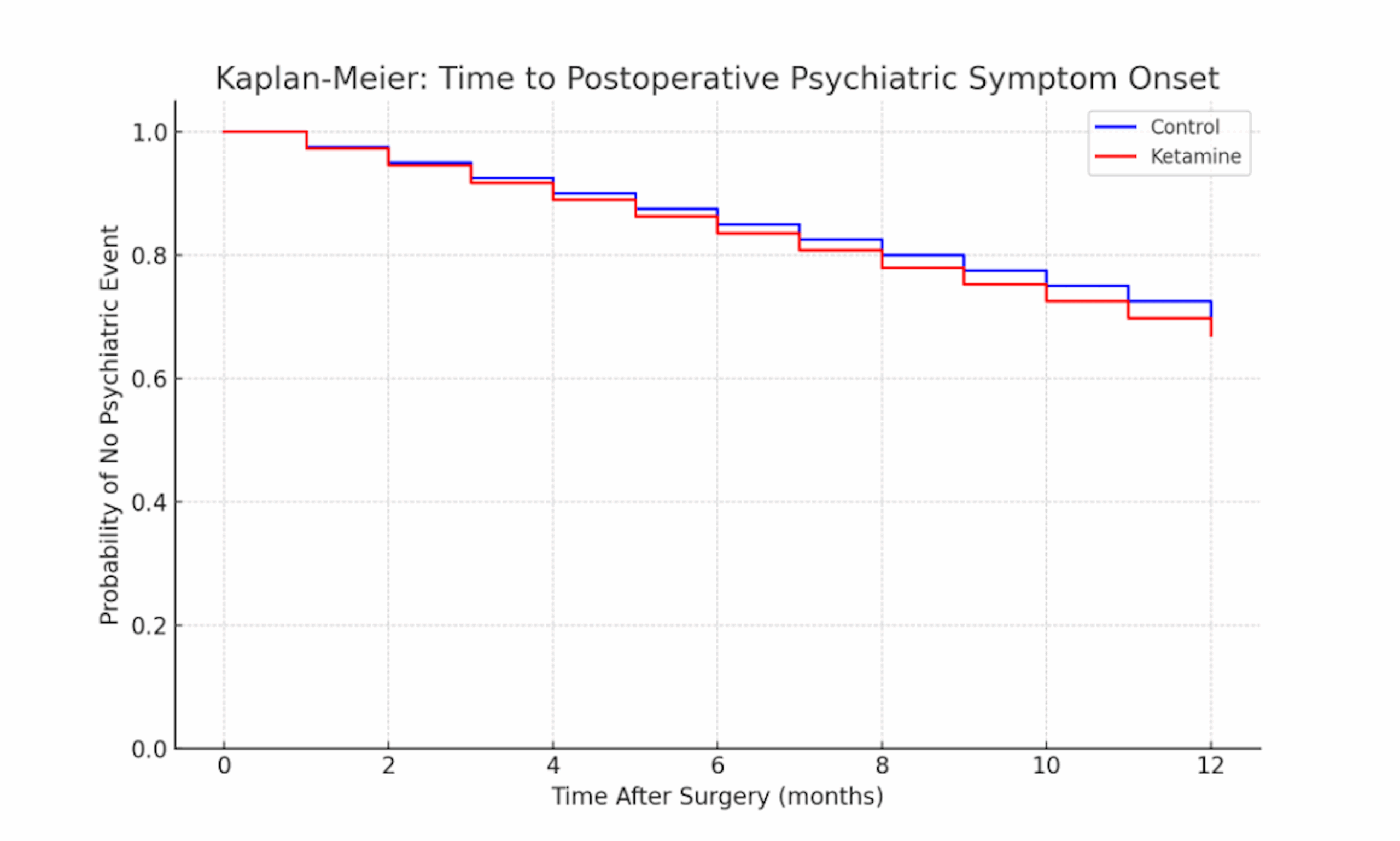

Clinically, the similarity of the survival curves for psychiatric symptom onset between groups further highlights ketamine’s limited impact. A Kaplan-Meier analysis of time to postoperative psychiatric symptom onset (Figure 3) showed overlapping trajectories for the ketamine and control groups. Median time-to-event (e.g., time to first document depressive or anxiety episode after surgery) did not differ appreciably by treatment. By 12 months post-THA, approximately one-third of patients in each group experienced a recurrence or worsening of depression/anxiety symptoms, and the hazard of symptom recurrence was statistically indistinguishable (log-rank P >0.5). In sum, the results suggest that a single intraoperative dose of ketamine did not significantly delay or prevent postoperative depression/anxiety relapse in this cohort, even when considering various age brackets, sexes, or specific psychiatric diagnoses. These findings provide a robust interpretation that ketamine’s expected prophylactic mood benefits were not realized in the context of elective hip replacement surgery, reinforcing the need to temper expectations regarding ketamine’s psychiatric benefits in perioperative care.

Figure 1: Incidence of postoperative depression by group

This bar chart compares the proportion of patients who experienced clinically significant depressive symptoms in the 6 months following surgery in the ketamine vs control groups. The ketamine group (red bar) had a slightly higher incidence of postoperative depression (approximately 24%) compared to the control group (blue bar, ~22%). Error bars (not shown for clarity) were comparable in magnitude, and the small absolute difference suggests no meaningful preventative effect of ketamine on postoperative depression. These data illustrate that intraoperative ketamine did not appreciably lower the risk of postoperative depressive episodes in this cohort.

Figure 2: Incidence of postoperative anxiety by group

This bar chart depicts the proportion of patients with significant anxiety symptoms in the postoperative period for the ketamine (red) and control (blue) groups. The incidence of anxiety was slightly higher in the ketamine-treated patients (~33%) than in controls (~30%), a paradoxical pattern given ketamine’s known anxiolytic properties in other settings. The minimal difference (roughly three percentage points) was not statistically significant, indicating considerable overlap between groups. Like postoperative depression, postoperative anxiety rates were not substantially reduced by ketamine; if anything, there was a trend toward higher anxiety incidence in the ketamine group, underscoring the absence of a clear protective effect.

Figure 3: Kaplan-Meier curve for time to postoperative psychiatric symptom onset in the ketamine vs control groups

This survival plot shows the probability over time that patients remain free of depressive or anxiety-related symptoms after surgery. The blue line (control) and red line (ketamine) start at 100% (all patients symptom-free at surgery) and decline as patients develop mood symptoms in the postoperative follow-up. Both groups exhibit a gradual decrease in symptom-free survival over 12 months, reflecting the cumulative incidence of mood episodes. The ketamine group’s curve (red) lies slightly below the control’s curve (blue) throughout, indicating a marginally faster time to symptom onset (i.e., a higher proportion of ketamine patients developed depression or anxiety sooner, although the difference is minor). By the one-year mark, roughly 65–70% of patients in each group remained free of a new or worsening psychiatric episode, with no significant difference between the curves (no hazard reduction with ketamine). The overlapping trajectories demonstrate that ketamine did not significantly prolong the time to postoperative depression or anxiety recurrence in this cohort.

Discussion

Ketamine usage is expanding beyond anesthesia to include pain management, procedural sedation, critical care, palliative care, and, most recently, mental health. Surgical therapy, particularly THA, is a major challenge for patients and has the potential to cause considerable psychological stress responses, such as sadness and anxiety. Postoperative depression and anxiety have been identified as major factors in total morbidity, longer hospitalization, and postoperative discomfort.[9] The hypothesis that ketamine has powerful antidepressant effects, particularly for postoperative patients, is an intriguing field of research. Recent research suggests that ketamine may be useful in improving depression and anxiety ratings in the near term after surgery. A 2023 meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled studies found substantial decreases in postoperative depression ratings on days one, three, seven, and at extended follow-up.[10] In addition, a recent narrative review emphasized intraoperative low-dose intravenous ketamine as having consistent short-term mood improvements among patients with preexisting depression.[11] More literature suggests that this benefit may be stronger for certain subpopulations, especially patients undergoing supratentorial brain tumor surgery and cervical cancer surgery.[11] Furthermore, a meta-analysis indicated that ketamine significantly decreased total opioid use and pain scores at 24 and 48 hours post-surgery, and also delayed the time to first opioid dose for orthopedic surgeries.[12]

Our study, however, showed that intraoperative ketamine use is associated with higher short-term psychiatric risk and earlier onset of symptoms in patients with MDD and GAD after THA. This challenges the notion that there are consistent therapeutic effects and efficacy of perioperative ketamine in reducing postoperative anxiety and depression in patients undergoing THA.

Various results regarding the effect of ketamine in pain management and psychiatric outcomes in the postoperative setting suggest that the answer is not straightforward. Our patient population was predominantly older, a demographic that carries higher risks of delirium and psychotomimetic side effects.[13] Therefore, this may contribute to the decreased therapeutic effects of intraoperative ketamine, as seen in our study. Ketamine may help prevent postoperative depression and anxiety in some clinical situations and may be more useful solely as an analgesic in others.[13] The age of patients undergoing THA frequently spans various age groups; however, a significant portion are middle-aged to older adults, with one study finding that 76.8% of THA patients were aged 45 and older.[13] Older individuals may be more vulnerable to ketamine’s dissociative and psychotomimetic side effects, including disorientation, dizziness, hallucinations, and nightmares. Ketamine can produce transitory elevations in blood pressure and heart rate, which is concerning for people who have prior cardiovascular disease, a typical comorbidity in older surgical patients. This heightened sensitivity to ketamine’s side effects in older adults may partly explain why perioperative ketamine use in patients undergoing THA did not confer benefits to those with preexisting MDD or GAD.

Our findings also raise important questions about the mechanisms underlying ketamine’s paradoxical or absent psychiatric benefits in this surgical cohort. While ketamine’s rapid antidepressant and anxiolytic properties are well-documented in psychiatric populations, the surgical stress response, characterized by neuroendocrine activation and systemic inflammation, may attenuate or override these effects.[14,15] Major surgery triggers inflammatory cytokine release and stress hormone surges that can precipitate depressive symptoms; ketamine’s NMDA receptor antagonism and promotion of BDNF-mediated synaptic plasticity may be insufficient to counteract this intense physiological stress.[16] The timing and dosing may also be critical: our study examined a single intraoperative dose, whereas repeated or postoperative administrations may be necessary to sustain mood benefits.[17] Moreover, patients receiving ketamine under general anesthesia do not experience the drug’s subjective dissociative state, which some researchers believe contributes to its antidepressant mechanism through psychological disruption of maladaptive thought patterns. Without this experiential component, ketamine’s neurobiological effects alone may not yield significant improvements in mood.

These mechanistic considerations have several clinical implications. First, the routine use of intraoperative ketamine as a psychiatric prophylactic in THA patients with MDD or GAD is not supported by our findings. It is consistent with prior trials that showed no preventive benefit in older surgical patients.[18] Second, anesthetic plans incorporating ketamine for analgesia in this population should be accompanied by awareness of potential neuropsychiatric side effects, especially in the elderly or those with significant anxiety disorders. Strategies such as concurrent use of benzodiazepines or α₂-agonists to mitigate emergence reactions may be prudent. Third, postoperative care pathways for THA patients with preexisting psychiatric illness should include early psychiatric follow-up, optimization of baseline psychiatric medications, and non-pharmacologic interventions to support recovery. Given the absence of benefit observed here, alternative approaches such as enhanced pain control, delirium prevention, and perioperative counseling may be more effective in reducing postoperative psychiatric morbidity. Finally, our subgroup analyses did not identify a demographic or diagnostic category that clearly benefited from ketamine; future research could focus on targeted protocols, such as repeated dosing in the immediate postoperative period, selective use in younger patients, or adjunctive multimodal psychiatric interventions.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that patients undergoing THA who have a prior diagnosis of MDD, GAD, or depressive episodes are at a significant risk of experiencing psychiatric symptoms postoperatively after receiving ketamine during surgery. We discovered a statistically significant acute rise in the occurrence of psychiatric symptoms among patients with existing MDD and GAD, compared to those without, in the postoperative phase. Current literature generally supports the use of ketamine in the perioperative setting due to its analgesic properties and its potential to improve postoperative psychiatric outcomes. However, these advantages may not be applicable in all surgical procedures. Our results suggest caution, especially in groups with vulnerabilities such as psychiatric history or age. There remain significant questions regarding the comprehension and application of ketamine in the context of those with pre-existing mental health disorders that should be further investigated.

One such area that should be further explored is patient-specific variables, such as age and psychiatric background, before the use of ketamine for THA. This is due to the complex psychiatric symptoms that may require more vigilant postoperative observation to mitigate the side effects of ketamine, including delirium, hallucinations, nausea, and vomiting. Furthermore, older adults and elderly patients may have an increased vulnerability to the neuropsychiatric effects induced by ketamine. The integration of geriatric-specific protocols and preoperative psychiatric evaluations may be critical measures in reducing postoperative complications within these demographics.

References

- Jaiswal P, Railton P, Khong H, Smith C, Powell J. Impact of preoperative mental health status on functional outcome 1 year after total hip arthroplasty. Can J Surg. 2019;62(5):300-304. doi:10.1503/cjs.013718

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Vajapey SP, McKeon JF, Krueger CA, Spitzer AI. Outcomes of total joint arthroplasty in patients with depression: A systematic review. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2021;18:187-198. doi:10.1016/j.jcot.2021.04.028

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Wilson JM, Farley KX, Erens GA, Bradbury TL, Guild GN. Preoperative Depression Is Associated With Increased Risk Following Revision Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(4):1048-1053. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2019.11.025

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Shin JW, Park Y, Park SH, et al. Association of Untreated Pre-surgical Depression With Pain and Outcomes After Spinal Surgery. Global Spine J. 2025;15(3):1725-1732. doi:10.1177/21925682241260642

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47(4):351-354. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00230-9

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Glue P, Neehoff S, Beaglehole B, Shadli S, McNaughton N, Hughes-Medlicott NJ. Ketamine for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder: Double-blind active-controlled crossover study. J Psychopharmacol. 2024;38(2):162-167. doi:10.1177/02698811241227026

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, Krystal JH. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:509-523. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-053013-062946

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Khan Z, Hameed M, Khan FA. Current role of perioperative intravenous ketamine: a narrative review. APS. 2023;1:36. doi:10.1007/s44254-023-00035-1

Crossref | Google Scholar - Drudi LM, Ades M, Turkdogan S, et al. Association of Depression With Mortality in Older Adults Undergoing Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(3):191-197. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2017.5064

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Guo J, Qiu D, Gu HW, et al. Efficacy and safety of perioperative application of ketamine on postoperative depression: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28(6):2266-2276. doi:10.1038/s41380-023-01945-z

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Radvansky BM, Shah K, Parikh A, Sifonios AN, Le V, Eloy JD. Role of ketamine in acute postoperative pain management: a narrative review. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:749837. doi:10.1155/2015/749837

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Riccardi A, Guarino M, Serra S, et al. Narrative Review: Low-Dose Ketamine for Pain Management. J Clin Med. 2023;12(9):3256. doi:10.3390/jcm12093256

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Kirkland E, Schumann SO, Schreiner A, et al. Patient Demographics and Clinic Type Are Associated With Patient Engagement Within a Remote Monitoring Program. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27(8):843-850. doi:10.1089/tmj.2020.0535

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Li S, Luo X, Hua D, et al. Ketamine Alleviates Postoperative Depression-Like Symptoms in Susceptible Mice: The Role of BDNF-TrkB Signaling. Front Pharmacol. 2020;10:1702. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01702

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(1):46-56. doi:10.1038/nrn2297

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Duman RS. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a new era in the battle against depression and suicide. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-659. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14344.1

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Chang HA, Wang YH, Tung CS, Yeh CB, Liu YP. 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone, a Tropomyosin-Kinase Related Receptor B Agonist, Produces Fast-Onset Antidepressant-Like Effects in Rats Exposed to Chronic Mild Stress. Psychiatry Investig. 2016;13(5):531-540. doi:10.4306/pi.2016.13.5.531

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Mashour GA, Ben Abdallah A, Pryor KO, et al. Intraoperative ketamine for prevention of depressive symptoms after major surgery in older adults: an international, multicentre, double-blind, randomised clinical trial. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121(5):1075-1083. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2018.03.030

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

None

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Rawan Elkomi

Department of Internal Medicine

Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, USA

Email: rawan.elkomi@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Tegshjargal Baasansukh, Chukwudalu Ononenyi, Malachi Scott, Liliana Light, Ayomide Ogunsakin

Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA

Syed Fahad Gillani

Department of Internal Medicine

Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, USA

Miriam Michael

Department of Internal Medicine

Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, USA

University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, USA

Authors Contributions

Tegshjargal Baasansukh and Syed Fahad Gillani contributed to conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, visualization, and drafting of the manuscript. Rawan Elkomi provided resources, data acquisition, clinical interpretation, validation, and critical review. Chukwudalu Ononenyi handled investigation, data extraction, project administration, and review. Malachi Scott contributed to data extraction, validation, statistical checking, visualization, and review. Liliana Light conducted the literature search, synthesized the background, and prepared the tables and figures. Ayomide Ogunsakin managed data, quality control, and replication of analyses. Miriam Michael, as senior author, contributed to the conceptualization, supervision, methodology, clinical oversight, project administration, critical review, and gave final approval, serving as guarantor of the work. All authors approved the final manuscript and accepted responsibility for its content.

Ethical Approval

This study analyzed exclusively de-identified electronic health records, as mandated by the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 45 and the HIPAA de-identification standard, which does not constitute human subjects research and was exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) review. Informed consent was not required.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Guarantor

The guarantor of this work is Miriam Michael.

DOI

Cite this Article

Baasansukh T, Gillani SF, Elkomi R, et al. The Impact of Intraoperative Ketamine on Postoperative Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Preexisting Depression and Anxiety Undergoing Total Hip Arthroplasty. medtigo J Anesth Pain Med. 2025;1(2):e3067127. doi:10.63096/medtigo3067127 Crossref