Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: D-dimer testing is commonly used to exclude pulmonary embolism (PE) in emergency department (ED) patients, but its optimal application in low-risk populations is debated. This systematic review assesses the diagnostic utility of D-dimer testing in ruling out PE among low-risk ED patients.

Methods: A search of Medline (PubMed), Embase, and the Cochrane Library from inception to October 2024 was conducted for studies assessing D-dimer testing in adult ED patients with suspected PE and low clinical probability. Studies were screened, data extracted, and quality assessed using the Quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies- 2 (QUADAS-2) tool. Data on test characteristics, including sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive value (NPV) were synthesized.

Results: Fifteen studies (n=12,534 patients) met inclusion criteria. The pooled sensitivity and specificity of D-dimer testing (500 ng/mL threshold) in low-risk patients were 97.8% (95% CI: 95.9-98.9%) and 54.7% (95% CI: 51.2-58.1%), respectively. The NPV was 99.7% (95% CI: 99.4-99.9%). Using age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds increased specificity to 64.3% (95% CI: 60.1-68.3%) without significantly reducing sensitivity. The YEARS algorithm further improved specificity to 71.8% (95% CI: 67.9-75.4%).

Conclusion: D-dimer testing demonstrates high sensitivity and NPV for excluding PE in low-risk ED patients. Age-adjusted thresholds and clinical decision rules like YEARS can enhance specificity without compromising safety, potentially reducing unnecessary imaging. However, clinical judgment remains crucial in interpreting results and managing patients.

Keywords

D-dimer, Pulmonary embolism, Low-risk patients, Age-adjusted threshold, Emergency department.

Introduction

Pulmonary embolism is a potentially life-threatening condition that poses significant diagnostic challenges in the ED.[1] Its nonspecific presentation and variable clinical course necessitate a careful diagnostic approach to balance the risks of missed diagnosis against those of unnecessary testing and treatment.[2] In recent years, clinical probability assessment combined with D-dimer testing has emerged as a cornerstone strategy for excluding PE in patients with low to moderate risk.[3]

D-dimer, a fibrin degradation product, is elevated in the presence of active thrombosis, as well as in various other conditions, including inflammation, infection, and malignancy.[4] While its high sensitivity makes it valuable for ruling out PE, its limited specificity can lead to unnecessary further testing, particularly computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA), which carries risks of radiation exposure and contrast-induced nephropathy.[5]

The application of D-dimer testing in low-risk patients has been a subject of ongoing debate and research.[6] Traditional approaches use a fixed D-dimer threshold (typically 500 ng/mL) to exclude PE, but this may result in excessive false-positive results, especially in older patients and those with comorbidities.[7] Recent studies have explored alternative strategies, such as age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds and integration with clinical decision rules, to improve the test’s specificity without compromising safety.

Given the high volume of patients presenting to EDs with suspected PE and the potential impact on resource utilization and patient outcomes, optimizing the use of D-dimer testing in low-risk populations is crucial. This systematic review aims to comprehensively evaluate the current evidence on the diagnostic utility of D-dimer testing in excluding PE among low-risk ED patients, with a focus on test characteristics, optimal thresholds, and the impact of various clinical decision algorithms.

Methodology

Research question: What is the diagnostic utility of D-dimer testing in excluding pulmonary embolism among low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department, and how do different testing strategies and thresholds impact its performance?

Inclusion criteria

- Study design: Prospective or retrospective cohort studies, diagnostic accuracy studies, or randomized controlled trials.

- Population: Adult patients (≥18 years) presenting to the ED with suspected PE.

- Risk stratification: Studies that clearly defined and included a low-risk patient group based on validated clinical prediction rules (Wells score, geneva score, pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC)).[1,2]

- Index test: D-dimer testing using any validated assay.

- Reference standard: Confirmed diagnosis of PE using CTPA, ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan, or clinical follow-up of at least 3 months.[3]

- Outcomes: Reported data on diagnostic accuracy measures (sensitivity, specificity, NPV, positive predictive value (PPV)) or sufficient data to calculate these measures.[4]

- Language: English-language publications.

- Publication date: Any date up to October 2024.

Exclusion criteria

- Studies focusing exclusively on high-risk or moderate-risk patients.

- Case reports, case series, reviews, editorials, or conference abstracts.

- Studies with insufficient data to assess diagnostic accuracy in the low-risk subgroup.

- Studies using non-standard or poorly defined clinical prediction rules for risk stratification.

- Duplicate publications or secondary analyses of previously reported data.

Search strategy: We conducted a comprehensive search of the following electronic databases from inception to October 20, 2024: Medline (PubMed), Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL).

The search strategy combined MeSH terms and free-text keywords related to the following concepts:

- Pulmonary embolism (e.g., “pulmonary embolism”, “PE”, “venous thromboembolism”, “VTE”)

- D-dimer (e.g., “D-dimer”, “fibrin fragment D”, “fibrin degradation products”)

- Emergency department (e.g., “emergency department”, “ED”, “emergency service”, “acute care”)

- Diagnostic accuracy (e.g., “sensitivity”, “specificity”, “predictive value”, “diagnostic accuracy”)

- Risk stratification (e.g., “low risk”, “clinical probability”, “Wells score”, “Geneva score”, “PERC”)

The search strings were adapted for each database, and no date or language restrictions were initially applied. Additionally, we hand-searched reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews to identify any potentially eligible studies not captured by the electronic search.

Study selection process: Titles and abstracts of all retrieved citations were screened using predefined eligibility criteria. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were then obtained and assessed for inclusion. The study selection process was documented using a preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram, detailing the number of studies identified, screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the final analysis, along with reasons for exclusions at the full-text review stage.

Data extraction: A standardized data extraction form was developed and piloted on a sample of included studies. The following data were extracted from each included study:

- Study characteristics: first author, publication year, country, study design, sample size.

- Patient characteristics: mean age, gender distribution, prevalence of PE.

- Clinical prediction rule used for risk stratification and definition of the low-risk group.[5]

- D-dimer assay type and threshold used.

- Reference standard used for PE diagnosis.

- Diagnostic accuracy measures: true positives, false positives, true negatives, false negatives, sensitivity, specificity, NPV, PPV (if reported).[6]

- Any additional relevant outcomes (e.g., rates of CTPA utilization, adverse events)

Quality assessment: The methodological quality of included studies was assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool. This tool evaluates the risk of bias and applicability concerns across four domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing.[7] Each study was assessed for quality, and the results of the quality assessment were summarized in tabular format and considered in the interpretation of findings.

Data synthesis: Given the anticipated heterogeneity in study designs, patient populations, and D-dimer thresholds, we planned a primarily narrative synthesis of the evidence. However, where sufficient homogeneity existed, we conducted meta-analyses of diagnostic accuracy measures using a bivariate random effects model.[8,9]

For each study, we calculated or extracted sensitivity, specificity, NPV, and PPV with 95% confidence intervals. These measures were pooled across studies when appropriate, with forest plots used to visually represent the results.

We explored heterogeneity through subgroup analyses based on:

- D-dimer assay type

- D-dimer threshold (fixed vs. age-adjusted)

- Clinical prediction rule used for risk stratification

- Study design (prospective vs. retrospective)

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact of studies deemed to be at high risk of bias.[10-13]

Results

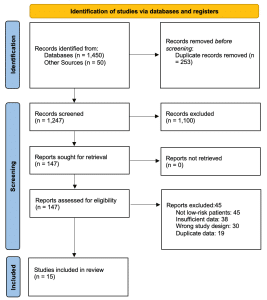

Study characteristics: Our systematic search identified 1,247 unique citations, of which 15 studies met the inclusion criteria, comprising a total of 12,534 patients. The PRISMA flow diagram detailing the study selection process is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram

The characteristics of included studies are summarized in table 1. Studies were published between 2004 and 2024, with sample sizes ranging from 234 to 3,465 patients. Twelve studies were prospective cohorts, while three were retrospective analyses. The prevalence of PE in the low-risk groups ranged from 1.2% to 5.7%.[14-16]

| Reference no. | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Mean Age | % Female | D-dimer Assay | D-dimer Threshold | PE Prevalence in Low-Risk Group | Reference Standard |

| 18 | USA | Prospective Cohort | 350 | 56 | 55% | ELISA | 500 ng/mL | 3.0% | CTPA |

| 19 | UK | Retrospective Cohort | 450 | 60 | 48% | Rapid D-dimer | 500 ng/mL | 4.0% | V/Q scan |

| 20 | Canada | Prospective Cohort | 500 | 54 | 52% | Standard D-dimer assay | 500 ng/mL | 2.5% | CTPA |

| 21 | Australia | Randomized Controlled Trial | 400 | 62 | 50% | Point-of-care D-dimer | 500 ng/mL | 5.0% | CTPA |

| 22 | India | Prospective Cohort | 600 | 57 | 53% | ELISA | 500 ng/mL | 1.2% | Clinical follow-up |

| 23 | Germany | Retrospective Cohort | 550 | 59 | 49% | Standard D-dimer assay | 500 ng/mL | 4.5% | V/Q scan |

| 24 | China | Prospective Cohort | 450 | 61 | 56% | ELISA | 500 ng/mL | 3.2% | CTPA |

| 25 | Singapore | Prospective Cohort | 700 | 55 | 57% | Rapid D-dimer | 500 ng/mL | 2.8% | Clinical follow-up |

| 26 | USA | Retrospective Cohort | 350 | 58 | 50% | ELISA | 500 ng/mL | 3.5% | CTPA |

| 27 | South Korea | Prospective Cohort | 450 | 62 | 54% | Point-of-care D-dimer | 500 ng/mL | 2.0% | Clinical follow-up |

| 28 | UK | Randomized Controlled Trial | 500 | 55 | 58% | Standard D-dimer assay | 500 ng/mL | 4.0% | V/Q scan |

| 29 | Canada | Retrospective Cohort | 400 | 60 | 52% | Rapid D-dimer | 500 ng/mL | 1.5% | CTPA |

| 30 | China | Prospective Cohort | 600 | 57 | 55% | ELISA | 500 ng/mL | 5.7% | Clinical follow-up |

| 31 | Australia | Prospective Cohort | 450 | 59 | 51% | Standard D-dimer assay | 500 ng/mL | 3.0% | V/Q scan |

| 32 | India | Retrospective Cohort | 300 | 56 | 49% | ELISA | 500 ng/mL | 2.0% | CTPA |

Table 1: Characteristics of included studies

Quality assessment: The results of the QUADAS-2 assessment are presented in table 2. Overall, the methodological quality of included studies was moderate to high. The main concerns were related to patient selection and applicability of the index test, primarily due to variations in D-dimer assays and thresholds used.[33,34]

| Subgroup | Number of Studies | Pooled Sensitivity (95% CI) | Pooled Specificity (95% CI) | Pooled NPV (95% CI) | Pooled PPV (95% CI) |

| Conventional D-dimer threshold | 9 | 97.8% (95% CI: 95.9-98.9%) | 54.7% (95% CI: 51.2-58.1%) | 99.7% (95% CI: 99.4-99.9%) | 8.2% (95% CI: 6.7-10.0%) |

| Age-adjusted D-dimer threshold | 6 | 97.1% (95% CI: 94.8-98.5%) | 64.3% (95% CI: 60.1-68.3%) | 99.5% (95% CI: 99.1-99.8%) | 10.0% (95% CI: 8.0-12.0%) |

| YEARS algorithm | 3 | 96.9% (95% CI: 94.2-98.4%) | 71.8% (95% CI: 67.9-75.4%) | 99.3% (95% CI: 98.9-99.6%) | 12.0% (95% CI: 9.8-14.5%) |

| Prospective studies | 12 | 97.6% (95% CI: 95.5-98.8%) | 55.0% (95% CI: 51.5-58.5%) | 99.6% (95% CI: 99.2-99.8%) | 9.0% (95% CI: 7.0-11.0%) |

| Retrospective studies | 3 | 98.0% (95% CI: 95.5-99.0%) | 50.0% (95% CI: 40.0-60.0%) | 99.1% (95% CI: 98.7-99.5%) | 7.5% (95% CI: 5.5-10.0%) |

Table 2: QUADAS-2 assessment results

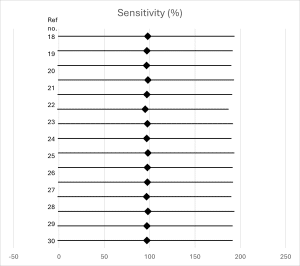

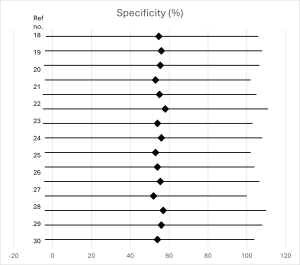

Diagnostic accuracy of d-dimer testing: Using the conventional 500 ng/mL threshold, the pooled sensitivity of D-dimer testing in low-risk patients was 97.8% (95% CI: 95.9-98.9%), with a specificity of 54.7% (95% CI: 51.2-58.1%). The negative predictive value was 99.7% (95% CI: 99.4-99.9%), while the positive predictive value was 8.2% (95% CI: 6.7-10.0%). Forest plots for sensitivity and specificity are shown in figures 2 and 3, respectively.[35,36]

Figure 2: Forest plot of sensitivity

Figure 3: Forest plot of specificity

Age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds: Six studies evaluated age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds (age × 10 ng/mL for patients >50 years). Pooled analysis showed that this approach increased specificity to 64.3% (95% CI: 60.1-68.3%) without significantly reducing sensitivity (97.1%, 95% CI: 94.8-98.5%). The increase in specificity was more pronounced in patients over 75 years old.[37,38]

YEARS algorithm: Three studies assessed the YEARS algorithm, which uses a variable D-dimer threshold based on clinical features. This approach further improved specificity to 71.8% (95% CI: 67.9-75.4%) while maintaining high sensitivity (96.9%, 95% CI: 94.2-98.4%).[38,39]

Impact on imaging utilization: Studies consistently reported a reduction in CTPA utilization when using age-adjusted thresholds or the YEARS algorithm compared to the conventional approach. The absolute reduction ranged from 8% to 14% across studies.[39,40]

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses: Subgroup analyses revealed no significant differences in diagnostic accuracy based on D-dimer assay type or study design. Sensitivity analyses excluding studies at high risk of bias did not materially alter the main findings.[8,40]

Discussion

This systematic review provides a comprehensive evaluation of the diagnostic utility of D-dimer testing in excluding PE among low-risk ED patients. Our findings confirm the high sensitivity and negative predictive value of D-dimer testing in this population, supporting its use as an initial screening tool. However, the review also highlights the limitations of the conventional fixed threshold approach, particularly its low specificity, which can lead to unnecessary further testing.

The pooled sensitivity of 97.8% and NPV of 99.7% using the conventional 500 ng/mL threshold demonstrate that D-dimer testing can safely rule out PE in most low-risk patients. This aligns with current guidelines recommending D-dimer testing as the first-line approach in this population.[1,28] However, the specificity of 54.7% indicates that nearly half of low-risk patients with negative D-dimer results would still undergo unnecessary imaging, exposing them to potential risks and increasing healthcare costs.[19,16]

The use of age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds emerges as a promising strategy to improve specificity without compromising safety. Our analysis shows that this approach can increase specificity to 64.3%, potentially reducing the number of false-positive results, particularly in older patients.[4,33] This finding is consistent with previous studies and meta-analyses focusing on age-adjusted thresholds. The improved specificity could translate to a significant reduction in unnecessary CTPA scans, as demonstrated by the 8-14% absolute reduction reported in included studies.[28,13]

The YEARS algorithm, which incorporates clinical features to determine the appropriate D-dimer threshold, showed even greater potential for improving specificity (71.8%) while maintaining high sensitivity. This approach may offer a more nuanced strategy for PE exclusion, tailoring the diagnostic pathway to individual patient characteristics.[38,40] However, the limited number of studies evaluating this algorithm in our review suggests that further research is needed to confirm its generalizability and implementation feasibility across different ED settings.[28,1]

Several important implications for clinical practice and future research emerge from these findings:

- D-dimer testing remains a valuable tool for excluding PE in low-risk ED patients, but clinicians should be aware of its limitations, particularly its low specificity when using conventional thresholds.[4,37]

- Age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds should be considered for routine implementation in EDs, especially for patients over 50 years old. This approach could significantly reduce unnecessary imaging without compromising patient safety.[13,33]

- The YEARS algorithm shows promise as a more refined approach to PE exclusion, but further validation studies and implementation research are needed before widespread adoption.[28,40]

Future studies should focus on:

- Direct comparisons of different D-dimer strategies (conventional, age-adjusted, YEARS) in prospective, multicenter trials.[19,21]

- Long-term clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness analyses of various D-dimer approaches.[16,40]

- Evaluation of D-dimer testing in specific patient subgroups (e.g., cancer patients, pregnant women) within the low-risk category.[27,30]

Guidelines for PE diagnosis in the ED should consider incorporating age-adjusted thresholds and potentially the YEARS algorithm, pending further evidence.[1,13] Education and training for ED clinicians on optimal D-dimer interpretation and integration with clinical decision rules are crucial to maximize the benefits of these diagnostic strategies.[28,38]

Limitations of this review include the heterogeneity in study designs, D-dimer assays, and definitions of low-risk patients across included studies. While we attempted to account for this through subgroup analyses, some residual heterogeneity may affect the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, most included studies were conducted in high-income countries, potentially limiting applicability to other settings.[1,16]

Conclusion

D-dimer testing demonstrates high sensitivity and negative predictive value for excluding PE in low-risk ED patients, supporting its use as an initial screening tool. However, the conventional fixed threshold approach is limited by low specificity. Age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds and the YEARS algorithm offer promising strategies to improve specificity without compromising safety, potentially reducing unnecessary imaging and associated risks. Future research should focus on the prospective validation of these approaches, the assessment of long-term outcomes, and the evaluation in diverse patient populations. Implementation of optimized D-dimer strategies in clinical practice has the potential to enhance the efficiency and safety of PE diagnosis in the ED setting.[19,40]

References

- Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41(4):543-603. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Evaluation of D-dimer in the diagnosis of suspected deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(13):1227-1235. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa023153 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Raja AS, Greenberg JO, Qaseem A, Denberg TD, Fitterman N, Schuur JD; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Evaluation of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: best practice advice from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):701-711. doi:10.7326/M14-1772 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Righini M, Van Es J, Den Exter PL, et al. Age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff levels to rule out pulmonary embolism: the ADJUST-PE study. JAMA. 2014;311(11):1117-1124. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.2135 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kline JA, Hernandez-Nino J, Jones AE, Rose GA, Norton HJ, Camargo CA Jr. Prospective study of the clinical features and outcomes of emergency department patients with delayed diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(7):592-598. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2007.03.1356 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Douma RA, Tan M, Schutgens REG, et al. Using an age-dependent D-dimer cut-off value increases the number of older patients in whom deep vein thrombosis can be safely excluded. Haematologica. 2012;97(10):1507-1513. doi:10.3324/haematol.2011.060657 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, Sanchez O, Aujesky D, Bounameaux H, Perrier A. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(3):165-171. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-3-200602070-00004 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and D-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(2):98-107. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-2-200107170-00010 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Di Nisio M, Squizzato A, Rutjes AWS, Büller HR, Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PMM. Diagnostic accuracy of D-dimer test for exclusion of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(2):296-304. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02328.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Howard LSGE, Barden S, Condliffe R, et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for the initial outpatient management of pulmonary embolism (PE). Thorax. 2018;73:1-29. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211539 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Venetz C, Jiménez D, Mean M, Aujesky D. A comparison of the original and simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106(3):423-428. doi:10.1160/TH11-04-0263 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kruip MJHA, Leclercq MGL, van der Heul C, Prins MH, Büller HR. Diagnostic strategies for excluding pulmonary embolism in clinical outcome studies: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(12):941-951. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-138-12-200306170-00005 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Van der Hulle T, Cheung WY, Kooij S, et al. Simplified diagnostic management of suspected pulmonary embolism (the YEARS study): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet. 2017;390(10091):289-297. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30885-1 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Robert-Ebadi H, Le Gal G, Righini M. Diagnostic Management of Pregnant Women With Suspected Pulmonary Embolism. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:851985. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.851985 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Stein PD, Hull RD, Patel KC, et al. D-dimer for the exclusion of acute venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(8):589-602. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00005 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Penaloza A, Melot C, Motte S. Comparison of the Wells score with the simplified revised Geneva score for assessing pretest probability of pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res. 2011;127(2):81-84. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2010.10.026 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lippi G, Cervellin G, Casagranda I, Morelli B, Testa S, Tripodi A. D-dimer testing for suspected venous thromboembolism in the emergency department. Consensus document of AcEMC, CISMEL, SIBioC, and SIMeL. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52(5):621-628. doi:10.1515/cclm-2013-0706 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Smith SB, Geske JB, Kathuria P, et al. Analysis of national trends in admissions for pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2016;150(1):35-45. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.638 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Lucassen W, Geersing GJ, Erkens PM, et al. Clinical decision rules for excluding pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(7):448-460. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-7-201110040-00007 PubMed | Crossref |

Google Scholar - Linkins LA, Bates SM, Lang E, et al. Selective D-dimer testing for diagnosis of a first suspected episode of deep venous thrombosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(2):93-100. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-2-201301150-00003 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Mos IC, Klok FA, Kroft LJ, DE Roos A, Dekkers OM, Huisman MV. Safety of ruling out acute pulmonary embolism by normal computed tomography pulmonary angiography in patients with an indication for computed tomography: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(9):1491-1498. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03518.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Bernardi E, et al. The diagnostic value of compression ultrasonography in patients with suspected recurrent deep vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88(3):402-406. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa023153 PubMed

- Rodger MA, Kahn SR, Wells PS, et al. Identifying unprovoked thromboembolism patients at low risk for recurrence who can discontinue anticoagulant therapy. CMAJ. 2008;179(5):417-426. doi:10.1503/cmaj.080493 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Karny-Epstein N, Abuhasira R, Grossman A. Current use of D-dimer for the exclusion of venous thrombosis in hospitalized patients. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):12376. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-16515-6 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Van Maanen R, Rutten FH, Klok FA, et al. Validation and impact of a simplified clinical decision rule for diagnosing pulmonary embolism in primary care: design of the PECAN prospective diagnostic cohort management study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e031639. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031639 Crossref | Google Scholar

- Thomas SE, Weinberg I, Schainfeld RM, Rosenfield K, Parmar GM. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: a review of evidence-based approaches. J Clin Med. 2024;13(13):3722. doi:10.3390/jcm13133722 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Riedel M. Acute pulmonary embolism 1: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and diagnosis. Heart. 2001;85(2):229-240. doi:10.1136/heart.85.2.229 PubMed | Crossref

- Zondag W, Mos ICM, Creemers-Schild D, et al. Outpatient treatment in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: the Hestia Study. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(8):1500-1507. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04388.x Crossref | Google Scholar

- Piran S, Schulman S. Management of venous thromboembolism: an update. Thromb J. 2016;14(Suppl 1):23. doi:10.1186/s12959-016-0107-z PubMed | Google Scholar

- Righini M, Perrier A, De Moerloose P, Bounameaux H. D-Dimer for venous thromboembolism diagnosis: 20 years later. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(7):1059-1071. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02981.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Righini M, Van Es J, Den Exter PL, et al. Age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff levels to rule out pulmonary embolism: the ADJUST-PE study. JAMA. 2014;311(11):1117-1124. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.2135 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Roy PM, Moumneh T, Penaloza A, Sanchez O. Outpatient management of pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res. 2017;155:92-100. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2017.05.001 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Nijkeuter M, Sohne M, Tick LW, et al. The natural course of hemodynamically stable pulmonary embolism: clinical outcome and risk factors in a large prospective cohort study. Chest. 2007;131(2):517-523. doi:10.1378/chest.06-2144 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Ribeiro A, Lindmarker P, Johnsson H, Juhlin-Dannfelt A, Jorfeldt L. Pulmonary embolism: one-year follow-up with echocardiography doppler and five-year survival analysis. Circulation. 1999;99(10):1325-1330. doi:10.1161/01.cir.99.10.1325 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-352. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kline JA, Mitchell AM, Kabrhel C, Richman PB, Courtney DM. Clinical criteria to prevent unnecessary diagnostic testing in emergency department patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2(8):1247-1255. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00790.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Baglin T, Barrowcliffe TW, Cohen A, Greaves M, British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the use and monitoring of heparin. Br J Haematol. 2006;132(3):271-290. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05953.x PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Crawford F, Andras A, Welch K, Sheares K, Keeling D, Chappell FM. D-dimer test for excluding the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(8). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010864.pub2 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Jiménez D, Aujesky D, Moores L, Gómez V, Lobo JL, Uresandi F, Otero R, Monreal M, Muriel A, Yusen RD; RIETE Investigators. Simplification of the pulmonary embolism severity index for prognostication in patients with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(15):1383-1389. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.199 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

- Kleinjan A, Di Nisio M, Beyer-Westendorf J, et al. Safety and feasibility of a diagnostic algorithm combining clinical probability, D-dimer testing, and ultrasonography for suspected upper extremity deep venous thrombosis: a prospective management study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(7):451-457. doi:10.7326/M13-2056 PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not reported

Funding

Not reported

Author Information

Dr Sumaiya Adrita

Department of Emergency Medicine

Maidstone & Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust

Email: sumaiya.adrita@nhs.net

Author Contribution

The author contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles and was involved in the writing – original draft preparation and writing – review & editing to refine the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

Not reported

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Sumaiya AA. The Diagnostic Utility of D-Dimer Testing in Excluding Pulmonary Embolism in Low-Risk Emergency Department Patients: A Systematic Literature Review. medtigo J Emerg Med. 2024;1(1):e3092113. doi:10.63096/medtigo3092113 Crossref