Author Affiliations

Abstract

Background: Inhalational anesthesia(IA) remains central to modern surgical practice, offering rapid onset, titratability, and reliable safety with agents like sevoflurane and desflurane. Technological innovations such as end-tidal control (EtC) systems enhance precision in anesthetic delivery. However, concerns remain regarding thermoregulation, emergence profiles, and postoperative complications.

Methodology: A systematic literature review was conducted across PubMed and Google Scholar to identify clinical studies from January 2020 to June 2025 evaluating IA. Inclusion criteria focused on human clinical trials and observational studies. Five high-quality studies met eligibility criteria based on the scale for the assessment of narrative review articles (SANRA) scores.

Results: EtC systems significantly improved target anesthetic delivery and reduced agent consumption. IA was non-inferior to total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) in intraoperative bleeding and hemodynamic control during endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS). Compared to remimazolam, inhalational agents were associated with lower rates of intraoperative hypothermia. Caffeine did not accelerate emergence in pediatric patients. No significant difference in postoperative delirium incidence was found between remimazolam and standard care.

Conclusion: IA continues to offer clinical advantages, especially with advancements like EtC. While its efficacy compares well with TIVA, limitations in thermoregulation and emergence variability remain. Tailored anesthetic strategies based on patient profiles and surgical context are essential. Further studies should focus on long-term outcomes and high-risk patient groups.

Keywords

Inhalational anesthesia, Total intravenous anesthesia, End-tidal control, Sevoflurane, Desflurane, Thermoregulation, Safety.

Introduction

IA remains a cornerstone of modern surgical practice, widely utilized for the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia across a broad spectrum of procedures.[1] Volatile anesthetic agents such as sevoflurane and desflurane are commonly employed due to their rapid onset, easy titratability, and established safety profiles. Delivered via advanced anesthesia machines, these agents enable precise control over anesthetic depth through adjustments in fresh gas flow (FGF) and end-tidal anesthetic agent (EtAA) concentrations. Their use is particularly advantageous in settings where rapid adjustment of anesthetic depth is critical, and their pharmacokinetic properties allow for swift recovery in most patients.[2,3]

Recent technological advancements, such as EtC systems, have enhanced the precision of inhalational anesthetic delivery. EtC automates the titration of anesthetic and oxygen concentrations based on continuous sampling of expired gases, helping clinicians maintain targeted EtAA and end-tidal oxygen (EtO₂) levels more effectively than manual controls.[4] Studies such as the Multicenter Automated System for Titration of End-tidal Regulation (MASTER) trial have demonstrated that EtC can achieve anesthetic delivery that is non-inferior to conventional methods, while also improving delivery accuracy and potentially reducing anesthetic consumption.[5] This innovation represents a significant advancement in patient safety and anesthetic efficiency, particularly in vulnerable populations such as the elderly or those with comorbidities.[6]

Despite these advantages, IA is not without challenges. One major concern is its role in perioperative thermoregulation. Hypothermia is a frequent complication of general anesthesia, occurring in up to 90% of patients, and can lead to adverse outcomes, including coagulopathy, surgical site infections, and prolonged recovery times.[7] Inhaled agents like desflurane and sevoflurane impair thermoregulatory control by depressing the body’s vasoconstriction and shivering thresholds. Furthermore, because anesthetized patients cannot compensate for cold exposure through behavioral responses, they are especially susceptible to hypothermia.[8]

The choice of an anesthetic can influence the severity of temperature dysregulation. For instance, desflurane, while favored for its rapid elimination and suitability for outpatient procedures, has not been well studied in terms of its thermoregulatory effects when compared with newer agents like remimazolam.[9] Some early studies suggest that remimazolam may better preserve core temperature than inhalational agents, although these findings are limited by confounding surgical variables. Comparative research examining desflurane and remimazolam under standardized surgical conditions, such as endoscopic nasal surgery, where external thermal influences are minimal, is needed to clarify these effects.[10]

IA is also frequently used in surgeries where maintaining an optimal surgical field is essential. In ESS, for instance, excessive intraoperative bleeding due to the richly vascularized sinonasal mucosa can significantly impair the visual field, increase operative time, and elevate the risk of complications.[11] The choice of anesthetic technique plays a role in intraoperative hemodynamics and bleeding control. Although TIVA has often been associated with better surgical field visibility due to more stable hemodynamics and reduced bleeding, recent studies suggest that IA, particularly when combined with remifentanil and sevoflurane, may offer comparable visibility.[12]

Sevoflurane, one of the most widely used volatile agents, is preferred in such cases for its low airway irritation, favorable cardiovascular profile, and fast recovery.[13] Unlike older agents such as isoflurane, sevoflurane appears to be non-inferior to TIVA when both are carefully managed. Moreover, the airway-protective properties and ease of administration of IA provide additional clinical advantages in high-risk patients. These factors support the continued relevance of inhalational agents in procedures like ESS, provided hemodynamic parameters and anesthetic depth are well controlled.[14]

Another area of clinical interest is the emergence from anesthesia, a phase marked by the patient’s return to consciousness and physiological homeostasis. Inhalational agents generally allow for smoother and more predictable emergence compared to some intravenous alternatives.[15] However, delayed awakening remains a potential concern, particularly in pediatric populations or patients with prolonged exposure to anesthetics. In this context, pharmacological adjuncts such as caffeine have gained attention. Acting as an adenosine receptor antagonist and central nervous system stimulant, caffeine has been shown to facilitate faster emergence from general anesthesia by enhancing neurotransmitter release and promoting arousal.[16]

While most studies on caffeine have focused on adult populations, recent investigations have begun exploring its safety and efficacy in children undergoing procedures such as inguinal herniorrhaphy. Early findings suggest that caffeine may accelerate the recovery process without introducing significant cardiovascular or neurological complications. The interaction between caffeine and inhalational agents, particularly in terms of awakening time and postoperative complications, remains an active area of investigation.[17]

Postoperative delirium (POD) is another postoperative concern that intersects with anesthetic choice. Common in elderly patients undergoing orthopedic procedures like hip surgery, POD is linked to prolonged hospital stays, functional decline, and increased mortality.[18] The use of benzodiazepines such as midazolam has been implicated in its pathogenesis due to GABAergic suppression.[19] Inhalational anesthetics, particularly sevoflurane, are frequently used in this demographic, yet their comparative impact on POD remains uncertain. Remimazolam has shown promise for its short half-life and limited respiratory effects, but evidence on its role in reducing POD is still emerging. Understanding how inhalational anesthesia influences POD risk is critical to optimizing outcomes in older surgical populations.[20]

IA plays a vital and evolving role in perioperative medicine. Its benefits in terms of ease of use, control over anesthetic depth, and airway protection are well established.[21] With advancements in delivery technology and growing insights into its thermoregulatory and neurocognitive effects, inhalational anesthesia continues to be refined for safer and more effective use. Ongoing comparative studies with newer agents and adjunctive therapies will further illuminate its role across various surgical contexts, particularly in populations at risk for complications such as hypothermia, delayed emergence, or postoperative delirium.[22,23]

Objectives

- To evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety of inhalational anesthetics in surgical settings.

- To assess technological advancements like EtC in optimizing anesthetic delivery.

- To examine the role of inhalational agents in perioperative hypothermia and thermoregulation.

- To compare inhalational anesthesia with TIVA regarding surgical field conditions and hemodynamic stability.

Methodology

A systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar databases to identify relevant studies addressing post-surgical pain following breast cancer treatment. The search strategy incorporated the terms: “Inhalational anesthesia”, and filters were applied to include clinical trials, randomized controlled trials, observational studies, and human Studies. The search included publications from January 1, 2020, to August 05, 2025, and was limited to studies published in English.

Inclusion criteria:

- Clinical trials, observational studies, and randomized controlled trials

- Studies involving human subjects

- Articles published in English

- Studies including male and female participants

- Studies published between January 1, 2020, and August 05, 2025

Exclusion criteria:

- Books, commentaries, editorials, letters, documents, and book chapters

- Case reports, case series, and literature reviews

- Articles published in languages other than English

- Animal studies and in vitro (laboratory) studies

- Articles published before January 1, 2020, or after August 05, 2025

- Studies lacking a reported results section

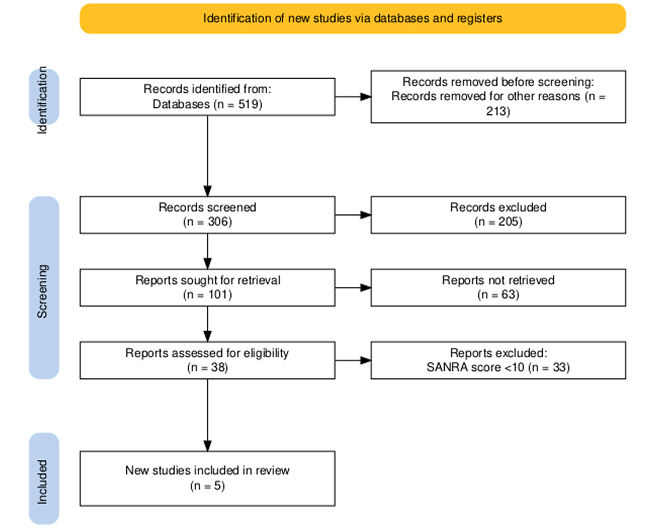

The initial search yielded a total of 519 records from databases. After the removal of 213 records due to duplication or other reasons, 306 records remained for screening. During the screening phase, 205 records were excluded based on titles and abstracts.

Out of the remaining 101 reports sought for retrieval, 63 could not be accessed due to unavailability or restricted access. The remaining 38 full-text reports were assessed for eligibility.

Of these, 33 studies were excluded due to a SANRA (Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles) score of less than 10, indicating insufficient methodological quality. Ultimately, five studies fulfilled all inclusion criteria and were included in the final review.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram

Results

Effect of remimazolam on postoperative delirium: A total of 833 patients undergoing hip surgery between January 2020 and March 2023 were initially screened. After applying exclusion criteria—patients under 65 years (n=216), alternative anesthesia (n=67), mixed anesthetic use (n=6), and reoperations (n=42), where 502 patients remained eligible for analysis. Following propensity score matching, 93 patients were included in each group: the remimazolam (R) group and the standard care (S) group.

Before matching, the R group had an older average age, more comorbidities, and higher transfusion rates than the S group. After matching, baseline characteristics were balanced between groups.

POD occurred in 161 of the 502 patients (32%). The incidence of POD did not significantly differ between groups either before (R: 33.7%, S: 30.7%; p = 0.475) or after matching (p = 1.000).

Univariate logistic regression analysis identified several variables potentially associated with POD, including male sex, polypharmacy, hypertension, lower hemoglobin and albumin levels, and elevated C-reactive protein(CRP). However, multivariate analysis revealed that remimazolam was not independently associated with POD incidence. In contrast, female sex was associated with a significantly lower risk of POD (p = 0.022; OR = 0.337; 95% CI: 0.133–0.853), while polypharmacy was significantly associated with increased POD risk (p = 0.047; OR = 1.092; 95% CI: 1.001–1.191).[24]

Effect of end-tidal control on clinical anesthesia performance: A total of 248 patients were initially enrolled in the study. Of these, 20 patients failed the screening questionnaires on the day of service, leaving 228 eligible participants who were randomized. Subsequently, eight patients withdrew before surgery due to changes in the anesthetic plan from general anesthesia to sedation (n = 4), unavailability of an Aisys CS machine equipped with EtC software (n = 3), or the absence of a trained anesthesia provider (n = 1). One additional patient crossed over from the EtC group to the manual control (MC) arm but was withdrawn because the clinician’s desired EtAA and Eto2 concentrations were not recorded, and steady state was not achieved. Another 10 patients were withdrawn after the procedure due to deletion of breath logs (n = 3) or failure to achieve steady-state EtAA or Eto2 concentrations (n = 7).

The final analysis included 210 patients, each of whom had at least 45 minutes of inhalational anesthesia data. Surgical procedures encompassed general surgery, gynecology, orthopedics, and otolaryngology. The median duration of surgery was similar across the two groups: 103 minutes (range 50–157) for the MC group and 94.5 minutes (range 58–151) for the EtC group (p = 0.361). The distribution of inhalational agents used was also comparable: desflurane was administered in 17% of MC cases and 27.5% of EtC cases; isoflurane in 13.4% of MC and 16.3% of EtC; and sevoflurane in 69.6% of MC and 56.1% of EtC. None of these differences was statistically significant. Median estimated blood loss was identical in both groups, reported at 25 mL (range 5–75 mL in MC and 5–50 mL in EtC) (p = 0.492).

In terms of accuracy in achieving target anesthetic concentrations, the EtC system maintained EtAA within the noninferiority limit for 98% ± 2.05% of the time, compared to 45.7% ± 31.7% for the MC group (p < 0.0001), representing a significant difference of 52.3% (95% CI: 45.9%–58.6%). For Eto2, EtC achieved the target range 86.3% ± 22.8% of the time, while the MC group achieved it 41% ± 33.3% of the time (p < 0.0001), a difference of 45.3% (95% CI: 36.1%–54.5%).

The EtC group also demonstrated a faster response time to achieve the initial desired EtAA concentration, with a median of 75 seconds (range 35–144), compared to 158 seconds (range 41–402) in the MC group (p = 0.0013), a significant difference of 62 seconds (95% CI: 20–128). Among the 32 subjects who qualified for evaluation of overshoot in the EtC arm, the median overshoot was 6.64% (range 4.9–9.42) of the desired EtAA. In contrast, the median overshoot in the MC arm was 0% (range 0–14.3), as many patients in this group failed to reach the target EtAA.

Deviation from the clinician’s target values also favored the EtC group. The median deviation from desired EtAA was 1.68% (range 1.29–2.42) in EtC versus 17.6% (range 11.2–28.5) in MC (p < 0.0001; difference: 15.7%, 95% CI: 13.5–19.0). Similarly, deviation from desired Eto2 was 1.63% (range 1.18–2.69) for EtC and 16% (range 7.2–28.4) for MC (p < 0.0001; difference: 13.7%, 95% CI: 10.5–18.9).

Inhalational agent consumption was reduced in the EtC group. Isoflurane usage decreased by 34% (p < 0.001) and desflurane by 31% (p = 0.025). Although sevoflurane usage decreased by 4% in the EtC group, this difference was not statistically significant. Fresh gas flow was determined by the clinician and was not restricted to low-flow rates in the MC group.

EtC deactivations were rare and transient. These included deactivation during vaporizer refills (n = 3), recalibration or reinstallation of the gas module (n = 3), and rapid target EtAA reductions at the end of cases (n = 4). Automatic deactivation occurred when the system detected higher-than-expected EtAA values for three breaths (n = 4) or detected low EtAA during the switch to bag mode (n = 1).

Seven protocol deviations were noted: four instances involved untrained staff performing procedures in the EtC group, and three instances in the MC group lacked recorded desired EtAA or Eto2 values. Upon review by the Data and Safety Monitoring Board, none of these deviations were deemed to compromise participant safety.[25]

Effect of anesthetic technique on intraoperative hypothermia: Out of 89 initially assessed patients, 19 did not meet the inclusion criteria, leaving 70 participants who were randomized into either the IA or R group. After excluding six patients with operating times under one hour, the final analysis included 64 patients—31 in the IA group and 33 in the R group.

Baseline characteristics were similar across both groups. Intraoperative data showed that the R group had a significantly higher rate of hypothermia compared to the IA group (63.6% vs. 32.3%; RR: 1.863; 95% CI: 1.16–3.110; effect size h = 0.637; p = 0.014). At the end of surgery, the core temperature in the R group was significantly lower (35.8 ± 0.6 °C) than in the IA group (36.3 ± 0.4 °C), with a mean difference supported by a 95% CI of 0.071 to 0.408 and an effect size d = 0.845 (p = 0.006).

While thermal comfort scores, incidence, and grading of postoperative shivering were comparable between groups, a significantly greater proportion of patients in the R group required the use of warming devices postoperatively (33.3% vs. 9.7%, p = 0.047).

Core temperature trends during the first hour of anesthesia induction were similar in both groups (P = 0.425). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) declined significantly from baseline in both groups at 15-, 30-, 45-, and 60-minute post-induction (Bonferroni-corrected p < 0.05), though intergroup differences were not significant (p = 0.201). In contrast, heart rate (HR) changes followed different patterns between the groups (p < 0.001): the IA group showed a consistent decline in HR at all time points compared to baseline, whereas HR remained stable in the R group. Postoperative outcomes and adverse event rates did not differ significantly between the two groups.[26]

Effect of anesthetic approach on blood loss and complications in endoscopic sinus surgery: Out of 122 patients initially screened, 110 were included in the final analysis following the exclusion of 12 individuals due to consent refusal (n=8), renal impairment (n=2), and uncontrolled hypertension (n=2). Participants were evenly distributed between two anesthetic regimens: 55 received inhalational anesthesia (IA) using sevoflurane-remifentanil, and 55 underwent total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) with propofol-remifentanil.

Baseline demographics, intraoperative characteristics, and Lund-Mackay scores—which reflect sinus disease severity—were comparable across both groups. The severity of sinus disease did not differ significantly (p = 0.489), and similar dosages of sufentanil (p = 0.416) and remifentanil (p = 0.320) were used between groups.

The primary outcome, intraoperative mean bleeding score (BS), demonstrated noninferiority of the IA regimen compared to TIVA (2.0 (1.7–2.2) vs 2.0 (1.8–2.1); p = 0.923). Additionally, no significant differences were observed in total blood loss (P = 0.986), bleeding rate (p = 0.359), or total fluid administration (p = 0.686). Hemodynamic parameters, including mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR), were also similar between groups (MAP: p = 0.214; HR: p = 0.344), as were other intraoperative and postoperative measures such as bispectral index (BIS), end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO₂), surgery duration, and post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) stay. Postoperative complications, including hypoxemia, sore throat, and nausea, showed no statistical differences between groups.

A post hoc subgroup analysis stratified patients based on sinus disease severity (Lund-Mackay score ≤12 vs >12). In both subgroups, intraoperative mean BS remained comparable between IA and TIVA, indicating consistent performance regardless of disease burden (p = 0.403 for LMS ≤12; p = 0.226 for LMS >12).[27]

Effect of caffeine on anesthetic emergence in pediatric patients: Out of 31 children initially assessed for inguinal herniorrhaphy under general anesthesia, 13 were excluded, resulting in 18 participants who completed the study. These patients were evenly assigned to either a caffeine or a placebo group.

Hemodynamic parameters—including diastolic and systolic blood pressure (DBP, SBP) and heart rate (HR)—were measured at multiple time points: anesthesia induction (T1), surgical incision (T2), time of intervention (T3), five minutes post-intervention (T4), and 30 minutes post-intervention (T5). Analysis using repeated measures ANOVA revealed no statistically significant differences between the two groups at any time point (p > 0.05).

The primary outcome, duration from anesthesia induction to laryngeal mask airway (LMA) removal, was nearly identical between groups (placebo: 44.77 ± 7.87 minutes; caffeine: 44.55 ± 10.68 minutes; p = 0.961).

Secondary outcomes included the time from drug administration to LMA removal, exit from the operating room, and recovery room discharge readiness. None of these metrics showed significant differences between groups (p = 0.467, p = 0.893, and p = 0.179, respectively).

No adverse events—such as nausea, vomiting, arrhythmia, cyanosis, or seizures—were reported in either group during the recovery period.[28]

| Study Title | Sample size | Study design | Population | Key findings | Limitations |

| Kim J et al.[24] | 502 analyzed (186 matched) | Retrospective cohort with propensity score matching | Elderly patients (≥65 years) undergoing hip surgery | No significant difference in POD between remimazolam and standard care groups. Polypharmacy ↑ POD risk; female sex ↓ risk. | Retrospective nature; unmeasured confounders possible; single center. |

| McCabe MD et al.[25] | 210 | Prospective randomized controlled trial | Adult surgical patients (general, ortho, gyne, ENT) | EtC is superior to manual control in maintaining target EtAA/Eto₂, faster response, and lower agent consumption. | Complex setup; crossover cases and protocol deviations; limited by equipment availability. |

| Cho SA et al.[26] | 64 | Prospective randomized study | Adults undergoing surgery >1 hr | Remimazolam is associated with significantly higher intraoperative hypothermia rates vs. inhalational anesthesia. | Small sample size; limited surgical variety; short observation duration. |

| Li H et al.[27] | 110 | Randomized controlled trial | Adults undergoing sinus surgery | IA is noninferior to TIVA in terms of bleeding score, blood loss, and complications; performance is stable across disease severity. | Single procedure type; surgical field assessment is subjective; limited to ASA I–III. |

| Yoo JH et al.[28] | 18 | Double-blind randomized placebo-controlled pilot study | Pediatric patients (inguinal hernia surgery) | No difference in emergence or recovery times between caffeine and placebo. No adverse events. | Small pilot study; limited power; narrow age range; not generalizable. |

Table 1: Comparative summary of reviewed studies on anesthetic techniques and outcomes

Discussion

In evaluating various aspects of anesthetic techniques and agents, the five studies present a nuanced understanding of efficacy, safety, and outcomes across diverse clinical scenarios. According to Kim J et al., the impact of remimazolam on postoperative delirium (POD) in elderly patients undergoing hip surgery was assessed. After rigorous matching to balance baseline characteristics, the incidence of POD did not differ significantly between the remimazolam (R) and standard care (S) groups. Their multivariate analysis further established that remimazolam was not an independent predictor of POD, while polypharmacy increased risk, and female sex was protective. This finding suggests that while remimazolam is safe from a cognitive recovery standpoint, it does not confer specific benefits in reducing POD compared to standard agents.[24]

In contrast, McCabe MD et al. focused on the precision of anesthetic delivery using end-tidal control (EtC) technology versus MC. Their randomized study showed that EtC significantly outperformed MC in maintaining target anesthetic concentrations for both EtAA and oxygen (EtO₂). EtC also reduced overshoot, time to target concentration, and volatile agent consumption, especially for isoflurane and desflurane. These results underscore the role of automation in enhancing the consistency and efficiency of anesthetic delivery, which stands in contrast to the pharmacologic focus of Kim et al.[25]

Cho SA et al. explored a different perioperative concern, which is intraoperative hypothermia, by comparing IA and remimazolam-based total intravenous anesthesia (R). They found a significantly higher incidence of hypothermia in the R group, alongside lower end-of-surgery core temperatures and increased postoperative warming device usage. These results suggest a thermoregulatory disadvantage of remimazolam-based anesthesia, which is particularly relevant in surgeries with prolonged durations. Interestingly, unlike the cognitive neutrality found in Kim et al., remimazolam here appeared inferior from a thermal homeostasis perspective.[26]

Li H et al. conducted a comparative study on IA versus TIVA in endoscopic sinus surgery, focusing on intraoperative bleeding and hemodynamic stability. Their results demonstrated non-inferiority of IA relative to TIVA in terms of bleeding scores, total blood loss, and other perioperative parameters. No differences in postoperative complications were observed. This contrasts with Cho et al.’s findings, where IA appeared superior in thermoregulation. Li et al.’s results reinforce the notion that both IA and TIVA are comparable in controlled bleeding environments such as sinus surgery, although patient-specific or surgery-specific considerations might tip the balance.[27]

Finally, Emami S et al. investigated a pharmacologic adjunct—caffeine—to expedite emergence from general anesthesia in pediatric patients. Their findings revealed no significant effect of caffeine on emergence times or discharge readiness. Furthermore, hemodynamic parameters remained stable and comparable between the caffeine and placebo groups, with no adverse events reported. In contrast to the McCabe et al. study, where a technological adjunct (EtC) yielded clear benefits in control and resource efficiency, Emami et al. demonstrated that pharmacologic stimulation with caffeine may not yield practical advantages in emergence within this clinical setting.[28]

Collectively, these studies highlight the multifactorial nature of anesthetic outcomes. While Kim et al. and Cho et al. emphasized the role of remimazolam in cognitive and thermoregulatory outcomes, respectively, McCabe et al. illustrated how technology could optimize anesthetic precision. Li et al. showed equivalence between IA and TIVA in a highly vascular surgical setting, while Emami et al. found no added benefit of caffeine in enhancing pediatric emergence. Together, these findings emphasize the need to tailor anesthetic approaches based on specific outcome priorities—be it cognitive protection, temperature regulation, hemodynamic stability, agent efficiency, or recovery kinetics.[24-28]

Limitations:

- Small sample sizes in some studies: Especially the study on caffeine in pediatric emergence (n=18) lacked statistical power to detect subtle differences.

- Heterogeneity of surgical procedures: Differences in procedure type (e.g., hip surgery vs. sinus surgery vs. herniorrhaphy) introduce variability in outcomes such as thermoregulation, bleeding, and anesthetic emergence.

- Potential confounding variables: Despite propensity score matching (e.g., in the remimazolam POD study), residual confounding from unmeasured variables like intraoperative medications, surgeon skill, or anesthetic depth may influence results.

- Short-term outcome focus: Most studies assessed immediate intraoperative or short-term postoperative outcomes (e.g., core temperature, POD, emergence time) but did not evaluate long-term cognitive function, morbidity, or quality of recovery.

- Lack of blinding in some interventions: Studies involving anesthetic delivery methods (manual control vs. EtC) or anesthetic agent choices may have unblinded clinicians, which can introduce performance or detection bias.

- Underrepresentation of high-risk populations: Many studies excluded patients with significant comorbidities, pediatric subgroups (beyond one caffeine study), or extreme age brackets, limiting generalizability to those populations.

- Limited evaluation of combined approaches: The synergistic or antagonistic effects of combining agents (e.g., remimazolam with volatile anesthetics) were not explored, although such combinations are used in clinical practice.[29,30]

Conclusion

IA remains a pivotal modality in perioperative care, offering precise control, airway protection, and favorable recovery profiles. Advances such as EtC systems enhance delivery accuracy and reduce anesthetic agent consumption. Comparative studies reveal that inhalational agents like sevoflurane remain non-inferior to TIVA in terms of surgical field visibility and hemodynamic stability. However, challenges such as thermoregulatory impairment and potential impacts on emergence and postoperative delirium persist. While pharmacologic adjuncts like caffeine show limited utility, anesthetic choice must be guided by patient characteristics, surgical context, and targeted outcomes. Continued research focusing on long-term recovery, cognitive impact, and high-risk populations is essential to refine anesthetic strategies for improved safety, efficacy, and patient-centered care across diverse surgical settings.

References

- Shui M, Xue Z, Miao X, et al. Intravenous versus inhalational maintenance of anesthesia for quality of recovery in adult patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery: A systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0254271. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0254271

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Öterkuş M, Dönmez İ, Nadir AH, et al. The effect of low flow anesthesia on hemodynamic and peripheral oxygenation parameters in obesity surgery. Saudi Med J. 2021;42(3):264-269. doi:10.15537/smj.2021.42.3.20200575

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - De Jong R, Shysh AJ. Development of a multimodal analgesia protocol for perioperative acute pain management for lower limb amputation. Pain Res Manag. 2018;2018:5237040. doi:10.1155/2018/5237040

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Hendrickx JFA, De Wolf AM. End-tidal anesthetic concentration: monitoring, interpretation, and clinical application. Anesthesiology. 2022;136(6):985-996. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000004218

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Sen E, Ganidaglı S, Mizrak A, et al. The effects of end-tidal controlled low-flow anesthesia on anesthetic agent consumption in elective surgeries: randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2025;25(1):176. doi:10.1186/s12871-025-03051-9

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Fu G, Xu L, Chen H, et al. State-of-the-art anesthesia practices: a comprehensive review on optimizing patient safety and recovery. BMC Surg. 2025;25(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12893-025-02763-6

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Ji N, Wang J, Li X, et al. Strategies for perioperative hypothermia management: advances in warming techniques and clinical implications: a narrative review. BMC Surg. 2024;24(1):425. doi:10.1186/s12893-024-02729-0

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Díaz M, Becker DE. Thermoregulation: physiological and clinical considerations during sedation and general anesthesia. Anesth Prog. 2010;57(1):25-34. doi:10.2344/0003-3006-57.1.25

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - McKay RE, Hall KT, Hills N. The Effect of Anesthetic Choice (Sevoflurane Versus Desflurane) and Neuromuscular Management on Speed of Airway Reflex Recovery. Anesth Analg. 2016;122(2):393-401. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000001022

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Cho SA, Ahn SM, Kwon W, Sung TY. Comparison of remimazolam and desflurane in emergence agitation after general anesthesia for nasal surgery: a prospective randomized controlled study. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2024;77(4):432-440. doi:10.4097/kja.23953

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Brunner JP, Levy JM, Ada ML, et al. Total intravenous anesthesia improves intraoperative visualization during surgery for high-grade chronic rhinosinusitis: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018;8(10):1114-1122. doi:10.1002/alr.22173

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Abdi A, Imani B, Zarei M, et al. The effect of isoflurane versus propofol-based total intravenous anesthesia on hemodynamic stability, intraoperative blood loss, surgical field quality, recovery characteristics, and complications in patients undergoing posterior lumbar fusion surgery: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2025;25(1):373. doi:10.1186/s12871-025-03254-0

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Brioni JD, Varughese S, Ahmed R, Bein B. A clinical review of inhalation anesthesia with sevoflurane: from early research to emerging topics. J Anesth. 2017;31(5):764-778. doi:10.1007/s00540-017-2375-6

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Jones PM, Bainbridge D, Chu MWA, et al. Comparison of isoflurane and sevoflurane in cardiac surgery: a randomized non-inferiority comparative effectiveness trial. Can J Anaesth. 2016;63(10):1128-1139. doi:10.1007/s12630-016-0706-y

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Bhaskar SB. Emergence from anaesthesia: Have we got it all smoothened out? Indian J Anaesth. 2013;57(1):1-3. doi:10.4103/0019-5049.108549

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Emami S, Panah A, Hakimi SS, et al. Effect of caffeine on the acceleration of emergence from general anesthesia with inhalation anesthetics in children undergoing inguinal herniorrhaphy: a randomized clinical trial. Iran J Med Sci. 2022;47(2):107-113. doi:10.30476/IJMS.2021.87688.1818

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Malviya AK, Saranlal AM, Mulchandani M, et al. Caffeine – Essentials for anaesthesiologists: A narrative review. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2023;39(4):528-538. doi:10.4103/joacp.joacp_285_22

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Chen Y, Liang S, Wu H, et al. Postoperative delirium in geriatric patients with hip fractures. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:1068278. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2022.1068278

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Engin E. GABA receptor subtypes and benzodiazepine use, misuse, and abuse. Front Psychiatry. 2023;13:1060949. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1060949

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Kim J, Lee S, Park B, et al. Effect of remimazolam versus propofol anesthesia on postoperative delirium in neurovascular surgery: study protocol for a randomized controlled, non-inferiority trial. Perioper Med (Lond). 2024;13(1):56. doi:10.1186/s13741-024-00415-6

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Tassoudis V, Ieropoulos H, Karanikolas M, et al. Bronchospasm in obese patients undergoing elective laparoscopic surgery under general anesthesia. Springerplus. 2016;5:435. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-2054-3

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Nathan N, Sperandio M, Erdmann W, et al. Le PhysioFlex: ventilateur de circuit fermé autorégulé d’anesthésie par inhalation à objectif de concentration. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 1997;16(5):534-540. doi:10.1016/s0750-7658(97)83349-7

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Verkaaik AP, Van Dijk G. High flow closed circuit anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1994;22(4):426-434. doi:10.1177/0310057X9402200418

PubMed| Crossref | Google Scholar - Kim J, Lee S, Yoo BH, et al. The effects of remimazolam and inhalational anesthetics on the incidence of postoperative hyperactive delirium in geriatric patients undergoing hip or femur surgery under general anesthesia: a retrospective observational study. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025;61(2):336. doi:10.3390/medicina61020336

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - McCabe MD, Dear GL, Klopman MA, et al. End-tidal control versus manual control of inhalational anesthesia delivery: a randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Anesth Analg. 2024;139(4):812-820. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000007132

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Cho SA, Lee SJ, Kwon W, et al. Effect of remimazolam on the incidence of intraoperative hypothermia compared with inhalation anesthetics in patients undergoing endoscopic nasal surgery: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Int J Med Sci. 2024;21(13):2510-2517. doi:10.7150/ijms.100262

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Li H, Du Y, Yang W, et al. Inhalational Anesthesia is Noninferior to Total Intravenous Anesthesia in Terms of Surgical Field Visibility in Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: A Randomized, Double-Blind Study. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2023;17:707-716. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S401750

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Yoo JH, Ok SY, Kim SH, et al. Comparison of upper and lower body forced air blanket to prevent perioperative hypothermia in patients who underwent spinal surgery in prone position: a randomized controlled trial. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2022;75(1):37-46. doi:10.4097/kja.21087

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Garg R, Gupta RC. Analysis of oxygen, anaesthesia agent and flows in anaesthesia machine. Indian J Anaesth. 2013;57(5):481-488. doi:10.4103/0019-5049.120144

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Pessano S, Gloeck NR, Tancredi L, et al. Ibuprofen for acute postoperative pain in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;1(1):CD015432. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD015432.pub2

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not applicable

Funding

Not applicable

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Samatha Ampeti

Independent Researcher

Department of Content, medtigo India Pvt Ltd, Pune, India

Email: ampetisamatha9@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Sonam Shashikala BV, Mansi Srivastava, Shubham Ravindra Sali, Nirali Patel, Raziya Begum Sheikh

Independent Researcher

Department of Content, medtigo India Pvt Ltd, Pune, India

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing, original draft preparation, and writing review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Sonam SBV, Samatha A, Mansi S, Shubham RS, Patel NK, Raziya BS. Optimizing Anesthetic Delivery: A Systematic Review of Inhalational Agents and Automation in Clinical Anesthesia. medtigo J Anesth Pain Med. 2025;1(2):e3067128. doi:10.63096/medtigo3067128 Crossref