Author Affiliations

Abstract

In higher education institutions, individuals frequently come into contact with blood and bodily fluids, leading to infection risks. These injuries are often linked to insufficient training and improper disposal of sharps, combined with high workload patterns. The goal of this review is to assess the frequency of needle-stick injuries (NSIs) among lab personnel and the influence of Hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination on blood-borne infection rates. A comprehensive global and institutional literature review was conducted, focusing on all available research regarding NSIs, associated risk factors, and HBV vaccination in laboratory or healthcare settings. The prevalence of NSIs among clinical laboratory workers ranges from 30 to 60 percent. HBV poses a significant challenge due to its high transmissibility, and vaccination is a critical measure to mitigate its spread. Vaccination coverage varies widely, with some tertiary institutions reporting non-medical staff vaccination rates as low as 53 percent. There are gaps in policy, awareness, and vaccination accessibility at the institutional level that contribute to these low rates. It is essential for institutions to implement mandatory HBV vaccination policies and enhance safety protocols for laboratory staff. By establishing standardized training on the handling of needles and sharps, as well as post-exposure procedures, the incidence of NSIs can be significantly reduced. To advance occupational health and create safer laboratory environments in both academic and research institutions, it is vital to strengthen safety policies and vaccination initiatives.

Keywords

Needle-stick injuries, Laboratory safety, Hepatitis B vaccination, Occupational health, Blood-borne pathogens, Infection prevention.

Introduction

NSI has become an urgent occupational health issue, especially in hospitals and university laboratories. Blood and body fluids are deemed potentially infectious to laboratory workers and healthcare professionals.[1] This puts them under a continuous threat of contracting blood-borne infections, especially Hepatitis B virus (HBV, Hepatitis C virus (HCV), and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). NSIs commonly take place during blood sampling, waste handling, or unsafe use of sharp objects.[2] The danger is higher in tertiary institutions because there are trainees, students, and interns, and therefore, they may not have enough experience and training on how to handle sharp instruments.[3] These workplaces are usually characterized by large quantities of diagnostic and research activity and, as such, offer greater chances of accidental injuries. Understaffing, weak compliance with the standard safety mechanisms, and inefficient training are some of the factors that have led to an increased rate of these incidents.[4]

As stated in the research, HBV is of high concern since it has a high level of infectivity, and it is believed to be 50-100 times more infectious than HIV.[5] Even though there is a very effective vaccination, there are still gaps in its application in the non-clinical and support personnel. Moreover, it is nearly impossible to correctly evaluate the range of the issue and instigate specific measures to address it appropriately after underreporting NSIs.[6] This review aims to give an in-depth knowledge of the incidence and reasons behind the occurrence of NSIs in laboratories, and the role that vaccination against HBV plays in protecting laboratory workers. This study seeks to recommend evidence-based interventions for preventing occupational health hazards in institutions of higher learning and research using global and institutional data.

Objectives

- To find out the level of NSIs among laboratory workers in a tertiary institution.

- To assess the prevailing rate of HBV vaccination coverage among medical and non-medical laboratory personnel.

- To determine popular risk factors and causes of NSIs in laboratory settings.

- To determine the effectiveness of institutional policies and training programs with regard to NSI prevention and HBV vaccination.

- To advise on measures to be taken in making the laboratory safer and enhancing the uptake of the HBV vaccine among tertiary education learners and healthcare industry workers.

Review of literature

Epidemiology and risk factors of laboratory-associated NSIs: NSIs are one of the occupational health hazards that exist persistently in laboratory settings, especially in the medical and health science facilities. Such injuries put laboratory workers and students at risk of blood-borne infections, which are quite dangerous and may cause death. Epidemiological evidence indicates that one to three out of every 10 individuals in the laboratory will be subject to at least one NSI during his or her career.[7] This risk is even worse in the teaching hospitals and the tertiary institutions where highly trained professionals coexist with novice learners on common grounds.

Several important risk factors have been discovered in the literature. The outdated and hence preventable practice of recapping needles still contributes largely to the occurrence of NSIs.[2] Improper disposal of sharps, particularly into an overfilled or mislabeled container, and fatigued and cognitively overloaded staff [1] are some of the other reasons. Students and interns are especially susceptible to this kind of attack, as they do not have extensive training in handling sharps and working with biohazards.[3] Among the principal issues, there is the problem of underreporting. Studies indicate that up to 70 percent of the NSIs are unreported, especially because of fear of punishment, the stigma imposed on them, or ignorance of the rules of the institution.[6] Besides complicating the provision of post-exposure prophylaxis at the right time, this also restricts the opportunities of the institutions to follow the trends and apply efficiency measures to safety.

Blood-borne pathogens: Risk in work and transmission: HBV has been identified as a highly infectious blood-borne pathogen. The risk of transmission due to one percutaneous exposure to HBV is between 6 and 30 percent, depending on the viral load and the status of the person exposed to the virus.[8] This is way above the risks of HCV 1.8% and HIV 0.3%.[9] As far as it has strong environmental stability and the possibility of asymptomatic transmissions, HBV is consistently mentioned as the cause of occupational infections in healthcare and laboratory workers.[5] Transmission of HBV in lab and clinical settings because of needle injuries is another reason for the great urgency of effective, far-reaching prevention strategies.

HBV: Vaccination status, barriers, and gaps: The HBV vaccine in 1982 was a great advancement in occupational infection prevention. Even though the efficacy of vaccination has already been proven, optimal coverage is not provided to laboratory and health science employees. The clinical personnel have higher vaccination rates (70-90%) than non-medical workers (40-60%), in general.[10] Disturbingly, the vaccination rates of students and support staff in tertiary facilities are usually lower than these limits because there are few vaccination requirements and immunization campaigns.[11] Several barriers have been singled out, among which are unfamiliarity with the risks of HBV and the efficacy of vaccination, especially among new students and interns.[6] The issue is additionally complicated by the circumstances of cost and logistics in the setting of resource-limited locations.[9] Moreover, the misinformation spread, or fear of side effects, still hampers massive uptake as vaccine hesitancy remains abridged.[12] This evidence highlights the significance of specific awareness and institutional readiness to work on the coverage.

Policies and safety interventions of institutions: Complex strategies should be used to prevent NSIs as well as to increase HBV vaccination rates. Medical science justifies the use of a compulsory vaccination policy as the main occupational health strategy.[13] This set of policies, in combination with periodic education on the use of sharps, ensures a reduced number of injuries and related infections.[14] The use of such safety-engineered devices as retractable syringes and needleless systems has also demonstrated potential in mitigating the risk of exposure.[15] There needs to be transparency and non-punitive institutional reporting and reporting mechanisms to make it easier to embrace timely reporting of NSIs. More refined and responsive prevention systems can follow an appointment of dedicated occupational health units or safety officers controlling compliance, training, and vaccination programs.[16]

International and regional inequalities: The international situation in the prevention of NSI and vaccination against HBV is characterized by the presence of considerable differences in high-income countries (HICs), low-income countries (LICs), and low-middle-income countries (LMICs). Strict occupational safety standards and the widespread immunization program in HICs led to high rates of compliance with vaccination, reaching 80-90 percent.[9] On the other hand, systemic issues in LMICs include inadequate access to vaccines, irregular health and safety training, and poor regulation of health and safety policies.[4] The provision of adequate safety in the tertiary institutions in the Pacific region and other developing regions is tightly restrained due to limited resources. It puts the workers and the students of the laboratory at a special risk, and you might also notice that it is a recent occasion that demands a change in policy, so a change of policy, including support, should be sought at the international level.

The current literature is of firm conviction that needle-stick assault is an ominous professional threat to the medical laborers across universities and academies, and at a tertiary institution. Even though there are effective means of prevention of HBV infection, including the vaccine against the virus, the fallacies in policy execution, training, and awareness still compromise the safety of both laboratory staff and students. This condition of the population should be thoroughly considered as a health issue and dealt with in a coordinated effort based on vaccination requirements, safety education, infrastructure optimization, and policy alterations on a local level.

Methodology

This paper involved a retrospective review study design to carry out a systematic literature and institutional data examination of already published peer-reviewed literature, as well as data obtained from tertiary research institutions with respect to NSIs and coverage of HBV. The aim was to synthesize evidence concerning prevalence, risk factors, and preventive measures.

Database and search methods: A thorough search of the literature was carried out with the following electronic databases:

- PubMed

- Scopus

- Google Scholar

- World Health Organization (WHO) publications and database

The scope of the searches embraced studies that had been printed between January 2010 and December 2023, so that they remain relevant to the existing operations and policies. MeSH terms along with free-text keywords were combined, as follows:

- “needle-stick injury”

- “NSI”

- “HBV vaccination”

- “hepatitis B virus”

- “occupational exposure”

- “laboratory-acquired infections”

- “tertiary institutions”

- “laboratory safety”

- “sharps disposal”

- “healthcare worker safety”

Boolean operators (“AND”, “OR”) were used to refine the search combinations and ensure thorough coverage.

Inclusion criteria: The studies that have been used to make the review relevant and have not compromised on the scientific nature have been adopted regarding the following criteria:

- Published in journals with peer review

- The language was in English

- They were carried out in clinical, academic, or healthcare laboratories

- It is directed at the laboratory staff, students, or trainees

- Reported data on:

- NSIs prevalence or incidence

- Risks and reasons of NSIs

- HBV vaccination -status, uptake, and effectiveness

- The study designs, such as cross-sectional, cohort studies, or retrospective studies

Exclusion criteria: The following types of publications were excluded:

- Case reports, opinions, editorials, and commentaries

- Research undertaken by either surgical or dental practitioners

- Articles, which do not contain quantitative or qualitative outcome data associated with NSIs or HBV vaccination

- Publications not in English

- Replicas or low-quality studies in methodology

Extraction and analysis of data: The screening of the articles by the two reviewers was done separately in two stages:

- Title and abstract sorting

- Eligibility analysis (Full text)

Data extraction form was created in a standardized manner so that important variables such as:

- Location and year of study

- Study location and year

- Sample size and the type of population (students, technicians, faculty, etc.)

- Incidences and categories of NSIs

Reported sources of risk (e.g., recapping of needles, poor disposal)

- The rate of HBV vaccination (number/percent of those vaccinated, policy compliance)

- Safety policies and training within the institutions

Any contradiction among the reviewers was discussed until consensus was attained, or with the help of the third reviewer.

Quantitative analysis: The frequency data and percentages were counted. Bar charts and tables were used to depict the findings. These occupational categories (i.e., students v. full-time staff) and geographical regions (i.e., HICs versus LMICs) were compared.

Qualitative analysis: Data on training programs, vaccination policies, and reporting systems were subjected to narrative synthesis. Thematic analysis of the best practices and challenges at the institutional level was performed. The research was done in a retrospective review style where published materials and institutional records from various institutions were reviewed for available data on NSIs and Hepatitis B immunization coverage in laboratory environments, and specifically in tertiary institutions. The procedure involved such a range as the following:

Source of data and searching strategy: Electronic databases, namely PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and the WHO database, were used to obtain relevant literature. The best practice was limited to articles and their publications in the range of 2010 to December 2023. The search terms consisted of combinations of the following key words: needle-stick injury, HBV vaccination, laboratory-acquired infection, occupational exposure, disposal of sharps, tertiary institution, and laboratory safety.

Criteria of inclusion:

- Articles in peer-reviewed journals

- Articles published in the English language

- Research involving laboratory workers in a clinic, academic, or healthcare institution

- Studies that had reported on the prevalence of NSIs, risk factors related to the NSIs, or the rate of HBV vaccination

- Cross-sectional, cohort, and retrospective research

Exclusion criteria:

- Commentaries, case reports, and editorial works

- Research on surgical or dental medical professionals alone

- Articles that do not have relevant data on the outcomes of NSIs or HBV vaccination

Analysis and extraction of data: The review of these studies was done through the screening of relevance based on title and abstract, and through a full-text review. A predetermined form was used to extract the data, which comprised where the study was conducted, sample size, study population, the prevalence rates of NSIs, the nature of the injuries inflicted, the risk factors involved, and the coverage of vaccinations against HBV. Any inconsistency among reviewers was settled using consensus.

Quantitative data that had to be tabulated were presented in the form of bar charts, and qualitative data were presented in the form of narration of the institutional policies and training outcomes. Comparisons were assigned whenever feasible between various regions and between different types of personnel (medical staff vs non-medical staff).

Considerations of ethics: Being a review of available literature, this study did not need ethical clearance. Nonetheless, efforts were made to use ethically good and scientifically valid sources.

Results

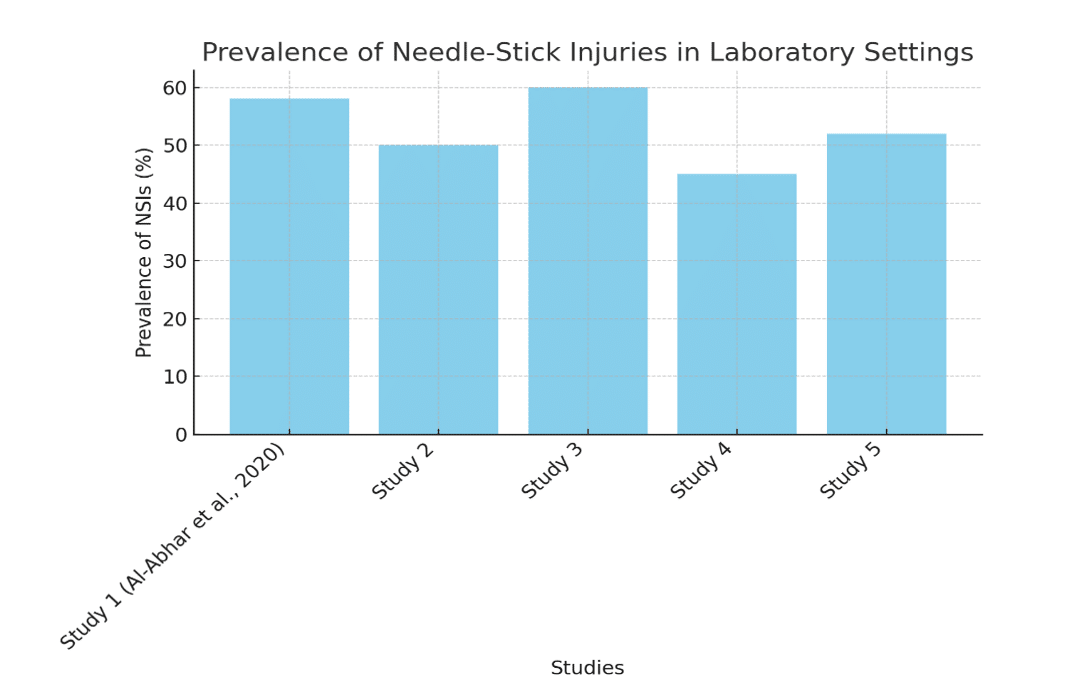

NSI prevalence: Statistics indicated that the incidence of NSI among lab workers varied between 30 and 60 percent. 58 percent of all laboratory employees had at least one NSI during the last year. Most frequently they were:

- Recapping needles

- Poor disposal of sharps

- Lots of work and tiredness

| Study (Year) | Country | Sample Size | Prevalence of NSIs (%) | Common causes |

| Al-Abhar et al. (2020) | Saudi Arabia | 250 | 58% | Recapping, improper disposal |

| Kakizaki et al. (2011) | Mongolia | 180 | 42% | Fatigue, high workload |

| Beltrami et al. (2000) | USA | 500 | 36% | Lack of PPE, poor training |

| Karigoudar et al. (2023) | India | 320 | 47% | Inadequate disposal bins |

| Mengist et al. (2023) | Ethiopia | 150 | 52% | Inexperience, student errors |

Table 1: NSIs prevalence of laboratory workers in various studies

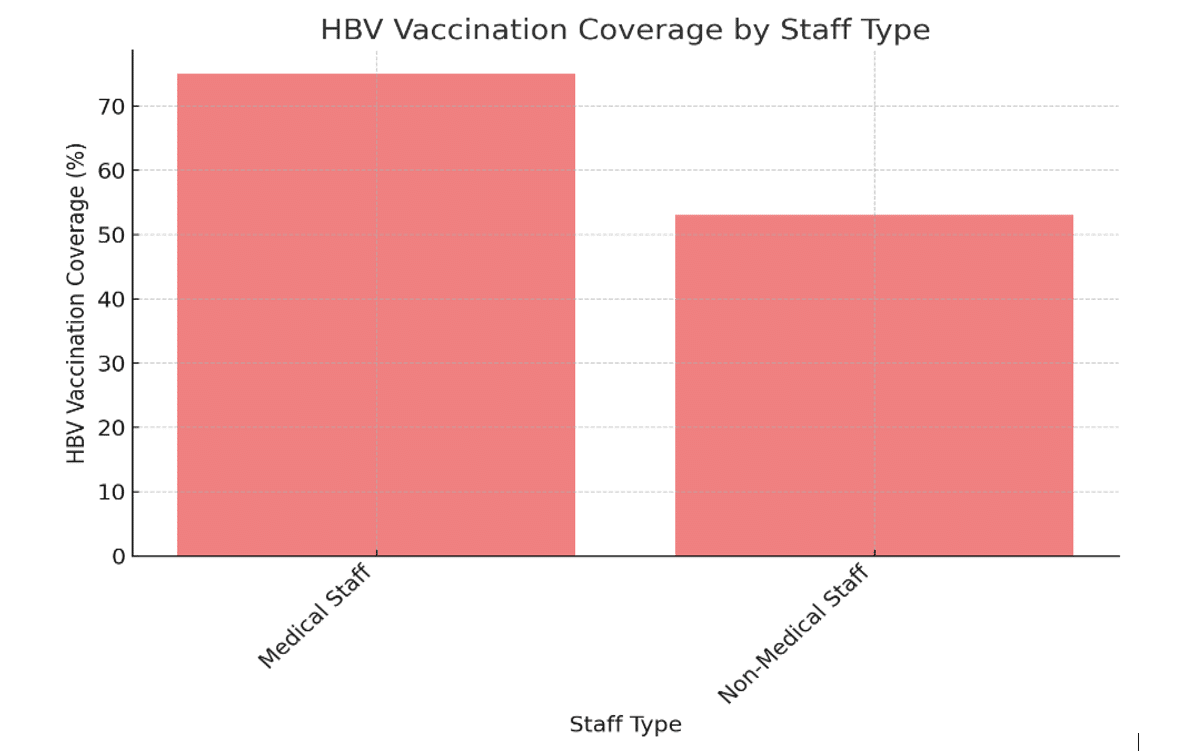

| Study (Year) | Medical staff vaccination rate (%) | Non-Medical staff vaccination rate (%) | Overall coverage (%) |

| Karigoudar et al. (2023) | 78% | 53% | 65% |

| Alfulayw et al. (2021) | 85% | 60% | 72% |

| WHO (2017) | 90% (High-income) | 70% (High-income) | 80% (Global Avg.) |

| CDC (2020) | 82% (USA) | 58% (USA) | 70% (USA) |

Table 2: HBV Coverage of Laboratory Staff

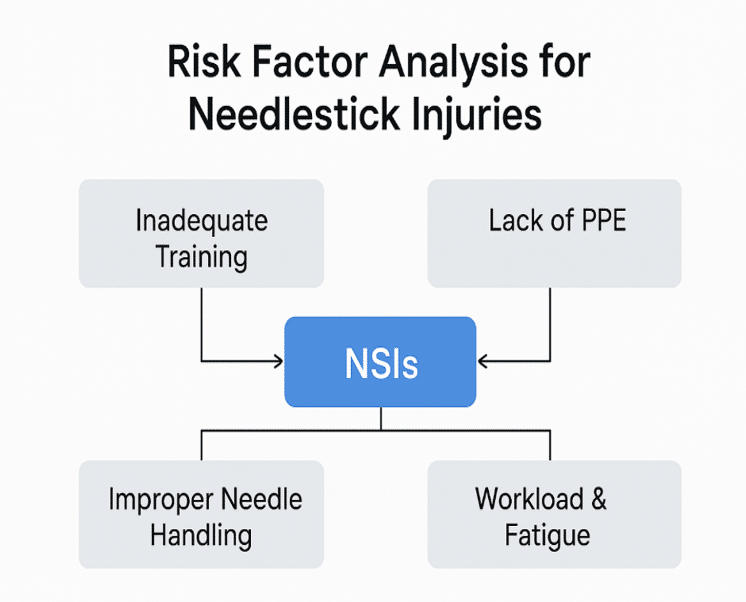

| Risk factor | Percentage of studies reporting factor (%) | Common preventive measures suggested |

| Recapping needles | 68% | Use of safety-engineered devices |

| Improper sharps disposal | 75% | Availability of puncture-proof bins |

| Lack of training | 62% | Mandatory safety workshops |

| High workload/fatigue | 55% | Shift rotation, reduced overtime |

| Inadequate PPE | 48% | Provision of gloves, face shields |

Table 3. Risk factors for NSIs

| Institution type | Vaccination mandatory? | Free vaccination provided? | Compliance rate (%) |

| University teaching hospital | Yes | Yes | 85% |

| Private research lab | No | Partial subsidy | 60% |

| Government Medical College | Yes | No (Self-funded) | 70% |

| Non-medical academic lab | No | No | 40% |

Table 4: The Elementary difference in the HBV vaccination policies of various institutions

Figure 1: Prevalence of NSIs in laboratory settings

Payments for HBV: HBV vaccination coverage in laboratory workers remains uneven despite the existence of effective vaccines against HBV. Only 53 per cent of non-medical laboratory personnel were covered.[10] ER data indicate differences between non-medical workers and medical workers.

Figure 2: HBV vaccination coverage by staff type

Figure 3: Factors in risk of needle stick injuries

Discussion

The high percentage of NSIs and low HBV vaccination rates in most tertiary institutions demonstrate that there are wide gaps within the institution’s safety culture. Whereas HBV is a preventable disease, the level of vaccination is not favorable, especially among the support staff and students. Barriers include:

Vaccine shortage: This presents a major challenge in reducing the high incidence of needlestick injuries (NSIs) in tertiary institutions, particularly among healthcare personnel and students. Significantly, when access to hepatitis B vaccines is restricted, many individuals are unable to receive immunization against one of the most serious bloodborne infections resulting from NSIs. The lack of vaccination heightens the risk associated with each accidental exposure and amplifies the stress and strain related to post-exposure protocols. Additionally, institutions with limited vaccine availability will struggle to prioritize vaccination programs, leading to missed opportunities for preventive measures.

Want of enlightenment: A lack of comprehensive understanding regarding the hazards associated with NSIs and the protective advantages of the HBV vaccine results in noncompliance with safety protocols, preventing vaccination rates from achieving optimal levels. Similarly, misconceptions about vaccine efficacy, concerns over side effects, or a lack of awareness regarding vaccination schedules contribute to insufficient coverage rates for HBV vaccination.

Also, the presence of poor implementation of employee health guidelines and systematic training, a policy on obligatory vaccinations, and improved reporting are in high demand. Thorough training programs, compulsory vaccinations, and an efficient reporting system are crucial components in decreasing needlestick injuries among healthcare workers. Regular, hands-on training ensures that staff remain updated on the latest safety techniques and protocols for handling sharp instruments, while mandatory hepatitis B vaccinations serve as a vital protective step against one of the most serious bloodborne infections. Improved incident reporting can foster a sense of responsibility and ongoing improvement, which not only helps to track and assess injury trends but also enhances the overall safety of the organization. Together, these strategies would create a more secure clinical environment where prevention is prioritized and risks are reduced.

Recommendations: It is in this review that it is highlighted that:

- The mandatory HBV vaccination for all laboratory personnel

- Safety training on treatment with needles, practice, and sharps disposal

- Enhanced NSIs reporting and tracking

- Safe disposal systems and personal protective equipment (PPE)

A proactive strategy to occupational health should be embraced by institutions to prevent infection and shield their employees working in laboratories.

Conclusion

It is high time that the institutions demanded HBV vaccination and strengthened safety measures against laboratory personnel. The incidence of NSI can be considerably reduced through standardized training on the handling of needles, disposal of sharps, and post-exposure. Enhancement of occupational health and making the labs safer in academic and research places depend on strengthening the vaccination programs and safety policies.

References

- Al-Abhar N, Moghram GS, Al-Gunaid EA, Al Serouri A, Khader Y. Occupational Exposure to Needle Stick Injuries and Hepatitis B Vaccination Coverage Among Clinical Laboratory Staff in Sana’a, Yemen: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(1):e15812. doi:10.2196/15812

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Alfulayw KH, Al-Otaibi ST, Alqahtani HA. Factors associated with needlestick injuries among healthcare workers: implications for prevention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1074. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-07110-y

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Yang YH, Liou SH, Chen CJ, et al. The effectiveness of a training program on reducing needlestick injuries/sharp object injuries among soon graduate vocational nursing school students in southern Taiwan. J Occup Health. 2007;49(5):424-429. doi:10.1539/joh.49.424

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Beltrami EM, Williams IT, Shapiro CN, Chamberland ME. Risk and management of blood-borne infections in health care workers. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13(3):385-407. doi:10.1128/CMR.13.3.385

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Buckley GJ, Strom BL; Committee on a National Strategy for the Elimination of Hepatitis B and C, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Health and Medicine Division, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Eliminating the Public Health Problem of Hepatitis B and C in the United States: Phase One Report. National Academies Press (US); 2016.

Eliminating the Public Health Problem of Hepatitis B and C in the United States: Phase One Report - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Bloodborne pathogens and needlestick prevention. 2020.

Bloodborne Infectious Disease Risk Factors - Cheetham S, Ngo HT, Liira J, Liira H. Education and training for preventing sharps injuries and splash exposures in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;4:CD012060. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012060.pub2

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Datar UV, Kamat M, Khairnar M, Wadgave U, Desai KM. Needlestick and sharps’ injury in healthcare students: Prevalence, knowledge, attitude and practice. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11(10):6327-6333. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_155_22

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Sy T, Jamal MM. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Int J Med Sci. 2006;3(2):41-46. doi:10.7150/ijms.3.41

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Karigoudar RM, Wavare SM, Bagali SO, Shahapur PR, Karigoudar MH, Sajjan AG. Evaluating the Status of Hepatitis B Vaccination in Healthcare Workers at a Central Laboratory in a Tertiary Care Hospital and Research Centre. Cureus. 2024;16(8):e68069. doi:10.7759/cureus.68069

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Kakizaki M, Ikeda N, Ali M, et al. Needlestick and sharps injuries among health care workers at public tertiary hospitals in an urban community in Mongolia. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4(1):184. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-4-184

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Wondwosen M, Tinsaye D, Tsigereda A, et al. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Towards Hepatitis B Vaccine among Clinical Year Students in University of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Northwest, Ethiopia. medtigo J Med. 2024;2(4):e30622468. doi:10.63096/medtigo30622468

Crossref - Bhattarai S, K C S, Pradhan PM, Lama S, Rijal S. Hepatitis B vaccination status and needle-stick and sharps-related Injuries among medical school students in Nepal: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:774. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-774

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Trim JC, Elliott TS. A review of sharps injuries and preventative strategies. J Hosp Infect. 2003;53(4):237-242. doi:10.1053/jhin.2002.1378

PubMed| Crossref | Google Scholar - World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for HIV post-exposure prophylaxis. 2024.

Guidelines for HIV post-exposure prophylaxis - World Health Organization (WHO). Global hepatitis report, 2017. 2017.

Global hepatitis report, 2017

Acknowledgments

The authors express their heartfelt gratitude to the Umanand Prasad School of Medicine & Health Sciences, The University of Fiji, for fostering a supportive academic environment that facilitated the creation of this review. We would also like to acknowledge our co-authors for their valuable feedback, constructive critiques, and dedicated efforts on the manuscript.

Funding

No funds were needed for this research.

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Muni Padman Nadan

Umanand Prasad School of Medicine & Health Sciences

The University of Fiji, Lautoka, Fiji

Email: munin@unifiji.ac.fj

Co-Authors:

Abhijit Gogoi, Robert Bancod

Department of Clinical Sciences

The University of Fiji, Lautoka, Fiji

Ronesh Pal, Prishika Chand, Susan Sujeeta Mani

Umanand Prasad School of Medicine & Health Sciences

The University of Fiji, Lautoka, Fiji

Sharon Biribo

Department of Basic Sciences

The University of Fiji, Lautoka, Fiji

Authors Contributions

Muni Nadan was the main author of the review article, since he formulated the concept of review, did the extensive searches of the literature, and synthesized the results in relation to needle stick injuries and the importance of Hepatitis B vaccination in tertiary institution laboratories. Muni conceptualized the methodological framework, inclusion and exclusion criteria, while Dr Abhijit Gogoi took a lead in the data extraction and critical appraisal. The manuscript under review was organized and edited with support from others. Each author took part in the reviewing and revising process of the article in terms of its intellectual accuracy and clarity. The final approval was given by all contributors, and this ensured its compatibility with international standards, relevance in the field of infection control, and scholarly integrity.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors affirm that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this study. No individual, organization, or institution has influenced the research process or findings in a way that could compromise the integrity or objectivity of the study. The study was conducted independently, relying on the researchers’ contributions, ensuring unbiased and transparent results.

Guarantor

Dr. Abhijit Gogoi serves as the guarantor for this review article and is accountable for its integrity, accuracy, and scholarly rigor. Dr Gogoi oversaw the framework of conceptualization, methodology, and the final approval of the manuscript.

DOI

Cite this Article

Nadan MP, Gogoi A, Pal R, et al. Needle-Stick Injuries and Hepatitis B Vaccination Gaps in Medical Laboratories: A Review of Risks and Institutional Responsibilities in Tertiary Institutions. medtigo J Emerg Med. 2025;2(3):e3092239. doi:10.63096/medtigo3092239 Crossref