Author Affiliations

Abstract

Introduction: Artificial intelligence (AI) has rapidly emerged as a transformative tool in anesthesiology, offering innovative solutions to enhance clinical decision-making, procedural accuracy, and patient safety. The field, which relies heavily on real-time interpretation of complex physiological data, stands to benefit significantly from AI-powered tools, particularly in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia (UGRA), depth-of-anesthesia (DoA) monitoring, and prediction of perioperative complications.

Methodology: A systematic review was conducted in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, analyzing literature from January 1, 2015, to June 30, 2025. PubMed and Google Scholar were searched, yielding 518 records. After exclusions, five high-quality studies were selected based on SANRA scoring.

Results: Studies demonstrated the utility of AI in various domains. ScanNav-assisted UGRA improved anatomical identification and training confidence. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) outperformed traditional monitors in classifying DoA states. Machine learning (ML) models accurately predicted postoperative sore throat and postinduction hypotension using multi-parametric clinical and echocardiographic data. Automated neuraxial ultrasound systems showed 79.1% first-pass success for spinal anesthesia, especially in obese patients.

Conclusion: AI enhances anesthetic practice by improving accuracy, personalization, and training outcomes. Despite challenges like interpretability and generalizability, AI-integrated tools show great promise in advancing perioperative care. Continued validation, ethical oversight, and workflow integration are essential for safe and effective implementation.

Keywords

Artificial intelligence, Anesthesiology, Machine learning, Ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia, Predictive modeling, Perioperative complications.

Introduction

The integration of AI into modern anesthesiology has emerged as a transformative advancement, offering novel tools to enhance clinical decision-making, optimize procedural accuracy, and improve patient safety.[1] Anesthesia is a field that inherently relies on the accurate interpretation of complex physiological data and the precise execution of techniques under time constraints and varying patient anatomies.[2] With AI-enabled technologies, particularly ML and deep learning (DL), anesthesiology is poised to experience a significant paradigm shift. From UGRA to neuraxial procedures, DoA monitoring, and the prediction of postoperative complications, AI provides solutions to challenges that have long constrained clinicians.[3]

One of the earliest domains in anesthesia to benefit from AI integration is ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. UGRA requires the acquisition and interpretation of real-time ultrasound images, a task that depends heavily on the operator’s expertise and familiarity with anatomy.[4] Even experienced anesthesiologists may face difficulties in interpreting sonographic images due to anatomical variations, patient factors such as obesity, or limitations in training.[5] Despite advancements in ultrasound image resolution, the improvement in user interpretability has not kept pace. This is where AI-powered image analysis becomes vital. Devices like Scannav Anatomy, peripheral nerve block, and Nerveblox employ DL to overlay anatomical color maps on B-mode ultrasound images, effectively guiding clinicians in identifying neural and vascular structures.[6] These systems aim to reduce variability in UGRA, support training, and enhance procedural success while minimizing the risks of inadvertent needle trauma to critical structures.[7]

Beyond regional anesthesia, AI has gained traction in one of the most crucial aspects of intraoperative management: monitoring the depth of anesthesia.[8] The anesthetic state is not universally defined, and current monitoring techniques, which are often based on hemodynamic variables, are imprecise and influenced by surgery type and pharmacologic agents. Electroencephalography (EEG), reflecting cerebral activity, offers a more direct assessment of consciousness.[9] Consequently, numerous EEG-derived indices, such as spectral edge frequency (SEF95), betaratio (BR), and entropy metrics, have been proposed and implemented in commercial DoA monitors like the bispectral index (BIS), index of consciousness (IoC), and M-entropy.[10] However, these monitors often rely on proprietary, nonlinear combinations of EEG parameters and may demonstrate inconsistencies in certain clinical scenarios. Moreover, no single EEG feature reliably tracks consciousness across all anesthetic depths.[11]

To address these limitations, recent research has turned to advanced AI methodologies. ANNs and support vector machines (SVMs) have demonstrated the capacity to synthesize multiple EEG-derived features, offering superior classification of anesthetic states. For instance, permutation entropy (PE), a robust nonlinear measure of EEG complexity, has been combined with SEF95, BR, and synchfastslow (SFS) indices as ANN inputs to predict BIS-based consciousness states with higher sensitivity and classification accuracy. These models not only surpass traditional single-index systems but also demonstrate the potential to customize anesthesia care based on individual patient responses, enhancing both safety and recovery outcomes.[12]

Similarly, machine learning has shown promise in addressing postoperative complications such as postoperative sore throat (POST), a prevalent issue following general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. POST, while often self-limiting, significantly impacts patient satisfaction, recovery, and healthcare utilization.[13] Conventional prediction of POST risk is limited by heterogeneity in patient characteristics and perioperative practices. AI, through ML algorithms trained on large and diverse datasets, offers a powerful tool to predict the occurrence of POST with high accuracy. By incorporating variables such as patient demographics, intubation details, and intraoperative parameters, predictive models can help identify at-risk individuals preemptively, enabling targeted prophylactic interventions and improving the overall perioperative experience.[14]

Intraoperative hypotension, another critical anesthetic concern, has been linked to adverse surgical outcomes and prolonged recovery. Its multifactorial etiology—including preexisting comorbidities, anesthetic agents, and hemodynamic variability—makes accurate prediction challenging.[15] Traditionally, clinicians have relied on simple clinical indicators and statistical models, which are often inadequate in real-time prediction. AI methods, particularly ML models trained in preoperative echocardiographic and intraoperative data, offer a more nuanced approach. These models can learn from subtle patterns and interactions in large datasets that are often invisible to conventional analyses.[16] Studies have shown that ML models incorporating echocardiographic parameters outperform traditional methods in predicting postinduction hypotension. As electronic health records and intraoperative monitoring systems become increasingly integrated, AI-driven predictive analytics hold immense promise in guiding individualized anesthetic management and preventing intraoperative crises.[17]

Another area where AI has made considerable strides is in enhancing neuraxial anesthesia. Traditionally performed using surface landmarks and tactile feedback, neuraxial procedures are susceptible to multiple needle passes, misidentification of spinal levels, and complications such as post-dural puncture headache or spinal hematoma. These risks are further amplified in obese patients, where anatomical landmarks are obscured.[18] Neuraxial ultrasound has improved the success rate of these procedures, but its utility is limited by operator proficiency in both image acquisition and interpretation. The steep learning curve and difficulty in pattern recognition of spinal structures hinder widespread adoption.[19]

Recent innovations have led to the development of AI-augmented ultrasound systems that automatically identify optimal insertion sites and needle trajectories for neuraxial blocks. These systems, using advanced image processing and ML algorithms, analyze ultrasound scans to detect key anatomical landmarks even in obese patients with a body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m².[20] Initial studies demonstrate that such systems can significantly improve first-pass success rates, reduce procedure time, and enhance clinician confidence. As AI continues to evolve, the prospect of fully automated spinal guidance systems is no longer distant, potentially revolutionizing spinal anesthesia and labor analgesia in complex patient populations.[21,22]

Taken together, these advancements underscore the rapidly growing influence of AI across diverse facets of anesthesiology. Whether enhancing the precision of regional and neuraxial blocks, improving intraoperative monitoring, predicting adverse events, or guiding decision-making through personalized analytics, AI offers unprecedented opportunities to optimize patient outcomes.[23,24] However, the translation of AI from research to clinical practice is not without challenges. Issues surrounding algorithm transparency, interpretability, data privacy, and clinician acceptance must be addressed to ensure responsible and effective implementation. Furthermore, the continuous evolution of AI technologies necessitates robust validation in real-world settings, interdisciplinary collaboration, and the development of guidelines to ensure safe integration into routine care.[25]

AI is reshaping anesthesiology into a data-driven, precision-focused specialty. Its applications, ranging from imaging and monitoring to prediction and decision support, are augmenting the capabilities of anesthesiologists and transforming patient care across the perioperative spectrum. As we move forward, the synergy between clinical expertise and AI innovation holds the key to delivering safer, smarter, and more personalized anesthesia services.[26]

This study aims to systematically evaluate the role of AI in anaesthesiology, with a specific focus on its applications in UGRA, DoA monitoring, and the prediction of perioperative complications. The objectives include analysing how AI-driven tools improve procedural accuracy, clinician training, and patient outcomes; comparing AI models with conventional approaches in monitoring and prediction; and identifying current challenges, such as interpretability and clinical integration, to guide future advancements in AI-assisted anesthetic care.

Methodology

A systematic literature search was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar databases according to PRISMA guidelines. The search included publications from January 1, 2015, to June 30, 2025, and was limited to studies published in English.

Inclusion criteria:

- Clinical trials, observational studies, and randomized controlled trials

- Studies involving human subjects

- Articles published in English

- Studies including male and female participants

- Studies published between January 1, 2015, and June 30, 2025

Exclusion criteria:

- Books, commentaries, editorials, letters, documents, and book chapters

- Case reports, case series, and literature reviews

- Articles published in languages other than English

- Animal studies and in vitro (laboratory) studies

- Articles published before January 1, 2015, or after June 30, 2025

- Studies lacking a reported results section

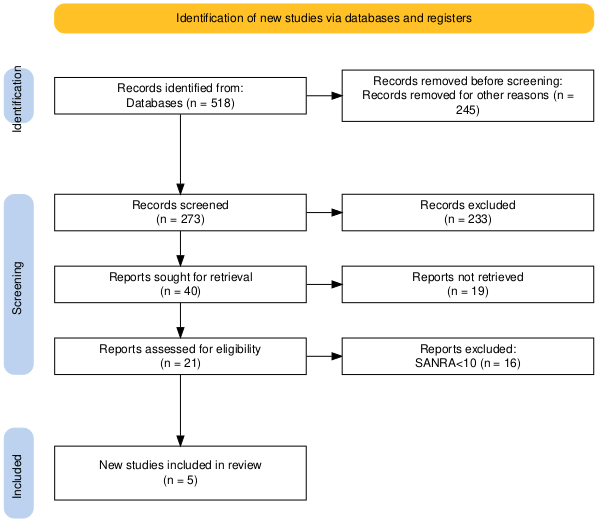

The study followed a systematic review methodology in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. Initially, a total of 518 records were identified through database searches. Before the screening process began, 245 records were removed for other reasons, leaving 273 records for screening. These records were screened based on their titles and abstracts, resulting in the exclusion of 233 records that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of the remaining 40 reports, full-text retrieval was attempted; however, 19 could not be retrieved due to access issues or unavailability. The remaining 21 full-text articles were then assessed for eligibility. During this phase, 16 articles were excluded because they scored below 10 on the SANRA, indicating insufficient methodological quality. Ultimately, five studies fulfilled all the inclusion criteria and were included in the final review.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram

Results

Effect of machine learning algorithms on predictive outcomes in anesthesiology

According to Bowness JS et al., a total of 240 ultrasound scans were conducted, 120 with ScanNav and 120 without. Among the ScanNav-assisted scans, 60 were performed by non-experts under expert supervision and 60 by experts. Both scan subjects were adult males aged 34 (Body mass index [BMI] 37.2 kg/m²) and 41 (BMI 28.9 kg/m²).

Non-experts gave more positive and fewer negative feedback responses compared to experts (p = 0.001). The most common positive feedback among non-experts was ScanNav’s contribution to their training (37/60, 61.7%), whereas experts highlighted its utility in teaching (30/60, 50%). In total, 70% reported that ScanNav helped identify key anatomical structures, and 63% believed it assisted in confirming correct ultrasound views. The most cited concern by non-experts was reduced confidence in scanning (4/60, 6.7%), while experts noted increased supervisor intervention (10/60, 16.7%).

Confidence levels among non-experts had a median of 6 (interquartile range (IQR) 5–8) without ScanNav and 7 (IQR 5.75–9) with ScanNav (p = 0.07). Expert confidence remained unchanged at a median of 10 (IQR 8–10) with or without ScanNav (p = 0.57). When supervising non-experts, experts rated their confidence in the non-experts’ scanning as a median of 7 (IQR 4.75–8) without and 8 (IQR 4–9) with ScanNav (p = 0.23). There was no significant difference in outcomes based on the scanned subject (p = 0.562).

For risk assessment, 103 of the 120 ScanNav-assisted scans were evaluated by both real-time and remote experts (17 scans were lost). Real-time users reported a potential increase in risk in 12/254 scans (4.7%) compared to 8/254 (3.1%) by remote experts (p = 0.362).[27]

Effect of AI on EEG-based anesthesia depth classification

According to the author Gu Y et al., to align with the BIS monitor’s 1-minute output frequency, six permutation entropy (PE) values each based on a 10-second data segment were averaged per minute. Four EEG-derived features were extracted from each 1-minute epoch and used as inputs to an ANN to classify the states of anesthesia: awake, light, general, and deep. To capture EEG dynamics effectively, different ANN architectures were tested using the empirical formula, where d is the number of hidden nodes, a and b are the number of input and output nodes, and c is a constant (1–10). The final ANN model included four layers: an input layer with four nodes, two hidden layers with four and seven nodes, respectively, and a single-node output layer.

To identify the optimal PE parameter m, values from 3 to 6 were evaluated. PE could effectively distinguish the awake, light, and general anesthesia states across all m values but failed to clearly identify the deep anesthesia state, which overlapped with general (for m=3–5) and light states (for m=6). Sensitivity and classification accuracy decreased as m increased, with the best performance at m=3, yielding an overall accuracy of 73.7% and a high sensitivity of 82.8% for detecting the awake state. However, sensitivity for detecting deep anesthesia was only 8%, indicating poor performance for this state.

Analysis showed that combining all four features achieved the highest classification accuracy, reinforcing the importance of multi-feature input for depth-of-anesthesia (DoA) monitoring. When comparing classifiers, ANN outperformed SVM with a classification accuracy of 79.1% (p = 0.044, z = 2.02) and consistently higher sensitivities across all anesthetic states.

Cross-validation results showed strong alignment between BIS and ANN-derived DoA indices, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.892. Bland–Altman analysis revealed a bias of 0.15 and limits of agreement between −16 and 16, indicating minimal bias and excellent agreement between BIS and the proposed ANN-based method.[28]

Effect of interpretable AI on post-anesthesia sore throat prediction

According to Zhou Q et al., a total of 961 patients were reviewed, with 834 ultimately included after applying exclusion criteria. These patients were divided into training (487), validation (198), and external validation (149) cohorts. The overall incidence of postoperative sore throat (POST) was 39.9%, with respective incidences of 41.7%, 38.4%, and 36.2% across the three cohorts. Significant differences between POST and non-POST groups were observed in variables such as age, sex, smoking status, blood pressure, endotracheal tube cuff pressure (ETCP), and time interval between extubation and the first drinking water after extubation (TIBEATFDWAE).

Feature selection using Boruta and least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) algorithms identified five key predictors: age, sex, ETCP, endotracheal tube insertion depth (ETID), and TIBEATFDWAE. These were used to build predictive models using Random Forest (RF), Neural Network (NN), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) classifiers. Hyperparameter optimization was performed, yielding optimal configurations for each model.

Model performance was assessed through the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), a precision–recall curve (AUPRC), Brier scores, and Log Loss across all cohorts. XGBoost demonstrated the highest net clinical benefit in the training cohort when the threshold probability exceeded 27%, while RF and NN outperformed it in the validation cohort. In the external validation cohort, NN had the best clinical utility with net benefits ranging from 60% to 80%.

Permutation feature importance analysis highlighted TIBEATFDWAE and ETCP as the most influential variables in RF and XGBoost, whereas NN identified sex and TIBEATFDWAE as top predictors. This suggests a strong association between TIBEATFDWAE and the likelihood of developing POST.

Model explainability using local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME) showed how individual features influenced predictions in specific patient cases. For example, case 1 had a 66% predicted risk of POST, associated with younger age, female sex, higher ETCP, extended TIBEATFDWAE, and improper ETID. In contrast, cases 2 and 3, with lower POST probabilities (16% and 15%, respectively), were characterized by older age, male sex, and shorter TIBEATFDWAE. Case 4 had a 55% POST risk, driven by favorable demographic factors but offset by lower ETCP and shorter TIBEATFDWAE. These findings underscore the importance of personalized prediction using interpretable machine learning models.[29]

Effect of AI-based models on early detection of anesthesia-induced hypotension

According to the study conducted by Yoshimura M et al., they analysed 6,849 adult patients undergoing noncardiac, non-obstetric surgeries under general anesthesia without preoperative intubation or continuous catecholamine use. After excluding patients without preoperative echocardiography within one month and those with echocardiography for non-preoperative purposes, 1,956 cases were included in the final analysis. Among these, 670 patients (34%) experienced postinduction hypotension. Data from 1,369 patients formed the training set, while 587 cases were allocated to the test set.

Using SHAP analysis, the feature set was reduced from 95 to 49 significant variables. The deep neural network (DNN) model demonstrated the best predictive performance on the test set, with an AUROC of 0.72 (95% CI: 0.67–0.76), outperforming XGBoost (0.54), LDA (0.56), and logistic regression (0.56). The DNN also showed a high positive predictive value of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.81–0.90), but a lower negative predictive value of 0.49 (95% CI: 0.43–0.55).

Decision curve analysis illustrated the clinical utility of the models across varying thresholds, and variable importance analysis via XGBoost identified key predictors, including ascending aorta diameter, transmitral flow A wave, heart rate, pulmonary venous flow S wave, tricuspid regurgitation pressure gradient (TVTRPG), inferior vena cava expiratory diameter (IVC) expiratory diameter, fractional shortening(FS), left ventricular (LV) mass index, and end-systolic volume.

Sensitivity analysis using an alternate definition of hypotension (MAP < 65 mmHg) showed reduced DNN performance (AUROC: 0.56, sensitivity and specificity: 64%), while other models (XGBoost, LDA, and LR) had AUROCs near 0.51–0.52, confirming DNN as the most effective model despite varying definitions.[30]

Effect of AI-Based Depth Estimation on Dural Puncture Efficiency

According to the author, In Chan JJ et al., 50 patients were enrolled between May 2018 and February 2019, with two later excluded due to opting for vaginal birth after Cesarean section. The final cohort included 48 patients with a mean age of 32.3 ± 4.8 years (range: 22–44) and an average BMI of 35.0 ± 4.5 kg/m².

Patients were categorized based on whether dural puncture was successful on the first attempt, as guided by the needle insertion site and angle determined by an automated program. Thirty-eight patients (79.1%, 95% CI: 65.0–89.5%) achieved success on the first attempt, while the remaining 10 patients required two (n=6, 12.5%), three (n=2, 4.2%), or four (n=2, 4.2%) attempts. BMI did not significantly differ between the groups.

Median scanning times for the L3/4 interspinous space and the posterior complex were 21.0 seconds (IQR: 17.0–32.0) and 11.0 seconds (IQR: 5.0–22.0), respectively. The average number of puncture attempts was 1.3 ± 0.75. Strong agreement was observed between the program-recorded and clinician-measured depth to the posterior complex, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.915 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.956.[31]

| Author | Sample size and population | AI technique/model used | Performance metrics | Outcomes |

| Bowness JS et al.[27] | 240 ultrasound scans: 120 with ScanNav (60 by experts, 60 by non-experts), 120 without; adult males aged 34 and 41 | Real-time image analysis using ScanNav | Confidence (median): non-experts 6 → 7 (p=0.07); experts unchanged (p=0.57); risk perception difference (p=0.362) | Non-experts found ScanNav helpful in training (61.7%); 70% said it aided anatomical recognition; experts used it more for teaching (50%) |

| Gu Y et al.[28] | EEG data aligned to BIS monitoring intervals (1-minute epochs with 6 PE segments) | ANN vs. SVM | Accuracy: 73.7% (best at m=3); ANN overall accuracy 79.1% (p=0.044); Awake sensitivity: 82.8%; Deep anesthesia: 8%; BIS correlation: r = 0.892 | ANN better than SVM; accurate classification of awake, light, general states; failed to clearly distinguish deep anesthesia |

| Zhou Q et al.[29] | 834 patients (training: 487, validation: 198, external validation: 149); general anesthesia cases | XGBoost, Random Forest (RF), Neural Network (NN) with LIME interpretability | AUROC: XGBoost highest in training; NN best in external validation; Net benefit: XGBoost > RF > NN (varied by cohort) | POST incidence ~40%; key predictors: TIBEATFDWAE, ETCP, age, sex; LIME showed patient-specific risk profiles; best predictors varied by model |

| Yoshimura M et al.[30] | 1,956 adult noncardiac, non-obstetric surgical patients; train: 1,369, test: 587 | Deep Neural Network (DNN), XGBoost, LDA, Logistic Regression | AUROC: DNN 0.72 (95% CI: 0.67–0.76); PPV: 0.86; NPV: 0.49; Others ≤ 0.56 | DNN best predicted post-induction hypotension; key features: aortic diameter, IVC diameter, LV mass, etc.; consistent across definitions |

| In Chan JJ et al.[31] | 48 patients (originally 50); mean age 32.3 ± 4.8 yrs; BMI ~35 | Automated depth estimation for needle placement | First-attempt success: 79.1% (95% CI: 65–89.5%); Pearson r = 0.915; Cronbach’s α = 0.956 | Strong match between predicted and actual depth; most punctures successful on first attempt; efficient scanning times |

Table 1: Comparative table of AI studies in anesthesiology

Discussion

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into anesthesiology is reshaping the field into a more precise, data-driven specialty. This discussion synthesizes the findings from multiple recent studies, emphasizing how AI and machine learning (ML) are transforming key areas of perioperative care, from procedural accuracy to complication prediction.

One of the most evident benefits of AI is in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia (UGRA). Bowness et al. evaluated the ScanNav system, which overlays anatomical color maps onto real-time ultrasound images using deep learning. Both experts and non-experts found it helpful, especially for teaching and training. While non-experts reported increased confidence and reduced anxiety about missing anatomical landmarks, experts noted that the tool helped facilitate instruction. However, real-time use sometimes led to concerns such as reduced autonomy and over-reliance on the software. Despite these limitations, the tool significantly supported procedural standardization, particularly for those still mastering UGRA.

In neuraxial anesthesia, similar AI-enhanced ultrasound tools are proving especially valuable for obese patients, where identifying spinal landmarks is notoriously difficult. In Chan et al.’s study, an automated image analysis program guided needle insertion and achieved a first-pass success rate of 79.1%. The correlation between automated and manual depth estimates was high, validating the system’s accuracy. This not only improves safety but also reduces procedural time and discomfort, which is especially relevant in obstetric anesthesia.

AI’s utility extends beyond procedural assistance to monitoring and predictive modeling. Gu et al. developed an artificial neural network (ANN) that used EEG-derived features to estimate depth of anesthesia (DoA). The ANN outperformed traditional systems like the bispectral index (BIS) in distinguishing awake and general anesthesia states but struggled with deep anesthesia, likely due to EEG variability and limited data. Nonetheless, the model showed high correlation with BIS, demonstrating potential for more nuanced and individualized anesthesia monitoring in the future.

In predicting postoperative sore throat (POST), Zhou et al. employed interpretable ML models like random forests, neural networks, and XGBoost. Using features such as endotracheal cuff pressure, insertion depth, and time to first water intake post-extubation, the models identified high-risk patients with significant accuracy. The use of model-agnostic explainability tools like LIME enhanced clinical interpretability and highlighted personalized risk profiles, a step forward in improving patient satisfaction and targeting prophylactic interventions.

Similarly, Yoshimura et al. explored ML applications in predicting postinduction hypotension, a frequent but potentially dangerous intraoperative event. Their deep neural network model, trained on preoperative echocardiographic data, significantly outperformed traditional models with an AUROC of 0.72. Features such as aortic diameter, transmitral flow, and heart rate were strong predictors. This approach supports proactive, individualized management and aligns with ongoing efforts to reduce hemodynamic variability.

Collectively, these findings underscore AI’s capacity to enhance safety, efficiency, and outcomes in anesthesiology. However, challenges remain. Model performance often varies based on patient population, data quality, and real-time applicability. Ensuring algorithm transparency, clinician trust, and integration into existing workflows will be key to widespread adoption. Future work should focus on multi-institutional validation, ethical deployment, and continued refinement to fully realize the potential of AI in anesthetic practice.

Limitations

- Limited generalizability: Most AI models in anesthesiology are developed and validated using data from single-center studies or homogeneous patient populations. This limits the ability of these models to perform reliably across varied clinical environments, institutions, and patient demographics.

- Data quality and heterogeneity: AI systems require large volumes of clean, annotated, and standardized data. However, real-world datasets often suffer from missing values, inconsistency in documentation, and variability in monitoring systems and clinical protocols. Such heterogeneity can hinder model training and reduce predictive accuracy.

- Lack of external validation: Many AI applications are evaluated in retrospective settings or controlled simulations without external validation. This raises concerns about their true clinical utility and safety in real-time, dynamic anesthetic scenarios.

- Interpretability and the “black box” problem: Deep learning algorithms, while powerful, often lack interpretability. Clinicians may be reluctant to trust or act upon recommendations from models whose decision-making process is not transparent, particularly in high-stakes environments like the operating room.

- Workflow integration challenges: Integrating AI tools into routine anesthetic practice involves technical and logistical barriers. These include the need for real-time computation, user-friendly interfaces, interoperability with electronic health record systems, and maintaining clinical efficiency.

Future directions

- Multicenter Data Collaboration: Build diverse, large-scale datasets across institutions for better model generalizability.

- Real-World Testing: Conduct prospective clinical trials to validate AI performance and clinical impact.

- Explainable AI: Focus on transparency using visual tools and interpretable algorithms to enhance clinician trust.

- Personalized Care: Use AI with genomic and health data to tailor anesthesia management

- System Integration: Embed AI into EHRs and monitors for real-time decision support.

- Ethics & Regulation: Develop clear ethical and legal frameworks to guide responsible AI use.

Conclusion

Artificial intelligence is revolutionizing anaesthesiology by enhancing precision, personalization, and safety across the perioperative continuum. From augmenting ultrasound-guided procedures and optimizing depth-of-anesthesia monitoring to predicting complications like sore throat and hypotension, AI enables data-driven, real-time clinical support. Studies consistently show improved accuracy, efficiency, and training benefits. However, challenges such as limited generalizability, interpretability, and workflow integration remain. Addressing these barriers through multicenter validation, ethical frameworks, and explainable AI will be key to sustainable adoption. The synergy between AI innovation and anaesthesiology expertise holds immense promise for delivering safer, smarter, and more individualized patient care.

References

- Singhal M, Gupta L, Hirani K. A comprehensive analysis and review of artificial intelligence in anaesthesia. Cureus. 2023;15(9):e45038. doi:10.7759/cureus.45038

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Harfaoui W, Alilou M, El Adib AR, et al. Patient safety in anesthesiology: progress, challenges, and prospects. Cureus. 2024;16(9):e69540. doi:10.7759/cureus.69540

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Lopes S, Rocha G, Guimarães-Pereira L, et al.Artificial intelligence and its clinical application in anesthesiology: a systematic review. J Clin Monit Comput. 2024;38(2):247-259. doi:10.1007/s10877-023-01088-0

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Viderman D, Dossov M, Seitenov S, et al. Artificial intelligence in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia: a scoping review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022; 9:994805. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.994805

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Das K, Sen J, Borode AS. Application of echocardiography in anaesthesia: from preoperative risk assessment to postoperative care. Cureus. 2024;16(9):e69559. doi:10.7759/cureus.69559

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Mika S, Gola W, Gil-Mika M, et al. Artificial intelligence-supported ultrasonography in anesthesiology: evaluation of a patient in the operating theatre. J Pers Med. 2024;14(3):310. doi:10.3390/jpm14030310

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - McLeod G, McKendrick M, Tafili T, et al. Patterns of skills acquisition in anesthesiologists during simulated interscalene block training on a soft embalmed Thiel cadaver: cohort study. JMIR Med Educ. 2022;8(3):e32840. doi:10.2196/32840

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Liu K, Qiu W, Yang X. Exploring the growth and impact of artificial intelligence in anesthesiology: a bibliometric study from 2004 to 2024. Front Med (Lausanne). 2025;12:1595060. doi:10.3389/fmed.2025.1595060

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Kertai MD, Whitlock EL, Avidan MS. Brain monitoring with electroencephalography and the electroencephalogram-derived bispectral index during cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2012;114(3):533-546. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e31823ee030

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Tobar E, Farías JI, Rojas V, et al. Electroencephalography spectral edge frequency and suppression rate-guided sedation in patients with COVID-19: A randomized controlled trial. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:1013430. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.1013430

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Li T, Huang Y, Wen P, Li Y. Accurate depth of anesthesia monitoring based on EEG signal complexity and frequency features. Brain Inform. 2024;11(1):28. doi:10.1186/s40708-024-00241-y

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Saeidi M, Karwowski W, Farahani FV, et al. Neural Decoding of EEG Signals with Machine Learning: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2021;11(11):1525. doi:10.3390/brainsci11111525

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Gupta B, Sahay N, Vinod K, Sandhu K, Basireddy HR, Mudiganti RKR. Recent advances in system management, decision support systems, artificial intelligence and computing in anaesthesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2023;67(1):146-151. doi:10.4103/ija.ija_974_22

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Arina P, Kaczorek MR, Hofmaenner DA, et al. Prediction of Complications and Prognostication in Perioperative Medicine: A Systematic Review and PROBAST Assessment of Machine Learning Tools. Anesthesiology. 2024;140(1):85-101. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000004764

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Paul K, Benedict AE, Sarkar S, Mathews RR, Unnithan A. Risk Factors and Clinical Outcomes of Perioperative Hypotension in the Neck of Femur Fracture Surgery: A Case-Control and Cohort Analysis. Cureus. 2024;16(11):e73788. doi:10.7759/cureus.73788

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Hassan AM, Rajesh A, Asaad M, et al. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Prediction of Surgical Complications: Current State, Applications, and Implications. Am Surg. 2023;89(1):25-30. doi:10.1177/00031348221101488

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - McDonnell JM, Evans SR, McCarthy L, et al. The diagnostic and prognostic value of artificial intelligence and artificial neural networks in spinal surgery: a narrative review. Bone Joint J. 2021;103-B(9):1442-1448. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.103B9.BJJ-2021-0192.R1

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Compagnone C, Borrini G, Calabrese A, Taddei M, Bellini V, Bignami E. Artificial intelligence enhanced ultrasound (AI-US) in a severe obese parturient: a case report. Ultrasound J. 2022;14(1):34. doi:10.1186/s13089-022-00283-5

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Shi L, Wang H, Shea GK. The Application of Artificial Intelligence in Spine Surgery: A Scoping Review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2025;9(4):e24.00405. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-24-00405

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Marino M, Hagh R, Hamrin Senorski E, et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia: An explorative scoping review. J Exp Orthop. 2024;11(3):e12104. doi:10.1002/jeo2.12104

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Han H, Li R, Fu D, et al. Revolutionizing spinal interventions: a systematic review of artificial intelligence technology applications in contemporary surgery. BMC Surg. 2024;24(1):345. doi:10.1186/s12893-024-02646-2

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Azimi P, Yazdanian T, Benzel EC, et al. A Review on the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Spinal Diseases. Asian Spine J. 2020;14(4):543-571. doi:10.31616/asj.2020.0147

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Hashimoto DA, Witkowski E, Gao L, Meireles O, Rosman G. Artificial Intelligence in Anesthesiology: Current Techniques, Clinical Applications, and Limitations. Anesthesiology. 2020;132(2):379-394. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000002960

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Matava C, Pankiv E, Ahumada L, et al. Artificial intelligence, machine learning and the pediatric airway. Paediatr Anaesth. 2020;30(3):264-268. doi:10.1111/pan.13792

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Patel NK, Samatha A, Mansi S, et al. Pharmacologic and Technologic Progress in Cardiac Anesthesia: Evidence from Recent Clinical Trials. medtigo J Anesth Pain Med. 2025;1(1):e3067118. doi:10.63096/medtigo3067118

Crossref - Kambale M, Jadhav S. Applications of artificial intelligence in anesthesia: A systematic review. Saudi J Anaesth. 2024;18(2):249-256. doi:10.4103/sja.sja_955_23

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Bowness JS, El-Boghdadly K, Woodworth G, et al. Exploring the utility of assistive artificial intelligence for ultrasound scanning in regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022;47(6):375-379. doi:10.1136/rapm-2021-103368

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Gu Y, Liang Z, Hagihira S. Use of Multiple EEG Features and Artificial Neural Network to Monitor the Depth of Anesthesia. Sensors (Basel). 2019;19(11):2499. doi:10.3390/s19112499

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Zhou Q, Liu X, Yun H, et al. Leveraging artificial intelligence to identify high-risk patients for postoperative sore throat: An observational study. Biomol Biomed. 2024;24(3):593-605. doi:10.17305/bb.2023.9519

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - Yoshimura M, Shiramoto H, Koga M, et al. Preoperative echocardiography predictive analytics for postinduction hypotension prediction. PLoS One. 2022;17(11):e0278140. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0278140

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar - In Chan JJ, Ma J, Leng Y, et al. Machine learning approach to needle insertion site identification for spinal anesthesia in obese patients. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021;21(1):246. doi:10.1186/s12871-021-01466-8

PubMed | Crossref | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments

Not applicable

Funding

Not applicable

Author Information

Corresponding Author:

Samatha Ampeti

Department of Pharmacology

Kakatiya University, University College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Warangal, TS, India

Email: ampetisamatha9@gmail.com

Co-Authors:

Sonam Shashikala BV, Mansi Srivastava, Shubham Ravindra Sali, Nirali Patel, Raziya Begum Sheikh

Independent Researcher

Department of Content, medtigo India Pvt Ltd, Pune, India

Authors Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, and data curation by acquiring and critically reviewing the selected articles. They were collectively involved in the writing, original draft preparation, and writing-review & editing to refine the manuscript. Additionally, all authors participated in the supervision of the work, ensuring accuracy and completeness. The final manuscript was approved by all named authors for submission to the journal.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable

Conflict of Interest Statement

None

Guarantor

None

DOI

Cite this Article

Sonam SBV, Samatha A, Mansi S, Shubham RS, Nirali P, Raziya BS. Artificial Intelligence Driven Innovation in Anesthesia for Personalized Perioperative Care. medtigo J Anesth Pain Med. 2025;1(2):e3067125. doi:10.63096/medtigo3067125 Crossref